One trait that unites book people (bibliographers, typographers, librarians, book conservators, graphic designers, collectors, book historians, printers, booksellers, curators, papermakers, bookbinders, etc…) is an emphasis on using an accurate terminology when describing aspects of the material book. The problem is that these sects have developed their own distinct usage, which sometimes overlap, and sometimes don’t. For example, the term “text block” means something entirely different to bookbinders and printers.

Booksellers and bibliographers often refer to Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors. Conservators are largely adopting the Language of Bindings from Ligatus, which is supposed to be available as a book from Oak Knoll soon. Binders usually use the lingo of the workshop where they learned the craft from. Printed resources include Etherington’s Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books and Glaister’s Encyclopedia of the Book.

Most of us learn our terminology haphazardly. Considered historically, prescriptive attempts at linguistic change often fail, even if what they propose is more rational or accurate. Given improvements in text searching, and the ease of taking and disseminating digital images, I wonder if the need to use a strict terminology is as important as it once was.

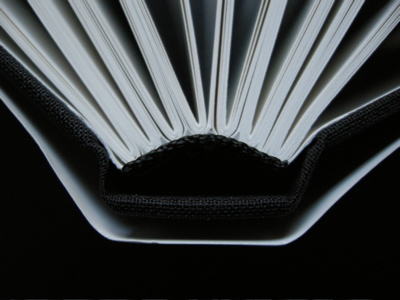

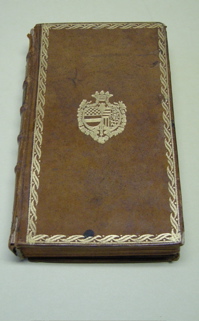

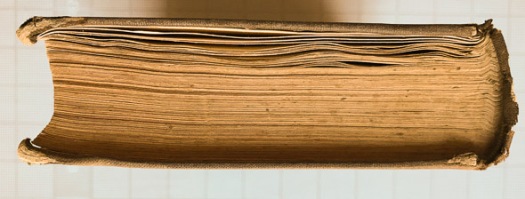

That said, I recently purchased a book that does not fit neatly into any existing descriptive framework that I’m familiar with. The distortions on the top edge of the book caught my attention when I looked at it in the store. Then I noticed the extremely crude backing, making it a useful “how-not-to” example when teaching. Many sections have two reverse folds! Then again, these reverse folds may have helped lock the sections into place, given the typical detaching of the spine linings: note the pages are not falling out at the foreedge. The binding itself is in good shape considering wear, even with an additional quarter inch or so of added material. The case binding structure is quite adaptable to different text block thicknesses.

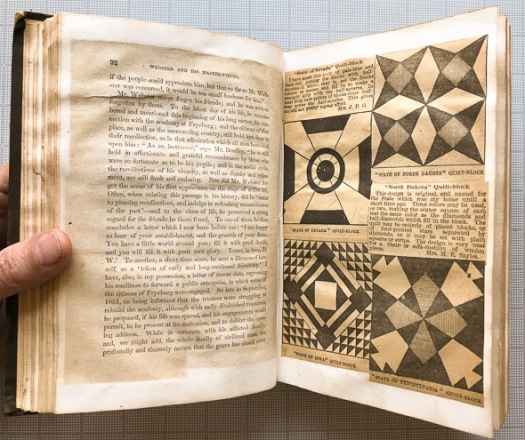

But the real reason I bought it was for the neatly glued in newspaper clippings of quilt patterns on the first twenty-four consecutive recto leaves. As in the example below, they typically completely cover the entire text block. The high quality of the text paper has helped buffer the newsprint, preserving it, though at the expense of the host: note the extensive staining on page 92, again quite typical.

It is not unusual for books to become repositories for all sorts of things: plants, leaves, receipts, scribbled notations, and the occasional hair-on mouse skin. I’m guessing the quilt patterns were added in the early 20th century. The additions cover and obscure the original text.

What to call it? Gary Frost, I think, would consider this in his broad rubric as an “intervention”. While it is certainly an altered book, I don’t think it has the artistic connotation that the phrase usually implies. It is not really a commonplace book, or an artist’s book. It is not extra-illustrated. It is more than a scrapbook, since the additions change the original book into something else.

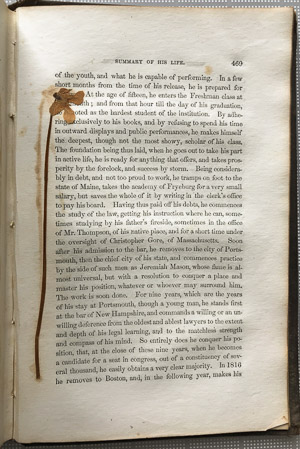

Originally the book was about Daniel Webster, who created the first American dictionary, and a dictionary documents the recorded usage of words. This particular copy was altered in a way that obliterates the text in order to become a reference for quilting. Even through there is some text on the quilting patterns, images dominate. Likely unintentionally, this book is a physical manifestation of the conflict between text and craft, the book learning verses practical activities, the head and the hand. How are books used? More than reading, it seems.

*****

While rereading this post, and looking through the book again, I noticed at least 22 pages near the end with pressed plants. Most seem to be intentionally arranged, resembling marginalia. or in this case the title page of the Doves Bible. Hmmm.