Peter Waters, in the introduction to “Boxes for the Protection of Rare Books: Their Design and Construction” established seven basic precepts for designing a protective enclosure in 1982. It is an excellent analysis of what a good book box should be, and is worth quoting in entirety:

“1. A good box should place the closed volume under light pressure so that is is unlikely to expand, become distorted, or shift position if the box is shaken or dropped.

2. The box should be strongly constructed so that if it sustains a blow any damage to the volume within will be minimized. (Shipping boxes need to be stronger and are not considered here.)

3. Materials used for making boxes should be of the highest permanence and durability, with appearance playing a lesser role than it would in the design of “presentation” boxes.

4. As far as possible, a book box, when assembled and covered, should be a single unit. Telescopic designs, for example, or boxes with inner sleeves and separate covers can confuse a user who must return each of several visually identical volumes to its own box.

5. The design and location of the label on a closed box should indicate clearly whether it should be shelved vertically or horizontally and how it should be opened. The method of opening and closing a box should always be simple and obvious. Inadequate directions for opening are potential sources of damage to the book.

6. When possible, a book box should be designed so that the user must remove it from the shelf and place it on a table to open it and must remove the volume with both hands. A slip case or telescopic case tempts a user to hold it with one hand while removing or replacing the volume with the other hand, which is potentially harmful to the book.

7. With few exceptions, a box design should restrain a user from opening the volume within the box.”

I would add two additional guidelines:

8. It should be cost effective and simple to construct.

9. Ideally, there should be no abrasion when removing or replacing the book in the box. Practically, this is often impossible.

Fig 1: A drop spine box with an integral cradle.

With these precepts in mind, I designed a box with an integral cradle. For collectors who read their books (not unheard of!), it is often ideal; most don’t want the hassle of storing or locating rare book room style wedges, and some open their books inside drop spine boxes anyway. This cradle could also be useful for book artists that want some control over how their books are displayed in an exhibition. In certain circumstances, it might even be useful in an institutional setting. Dedicated cradles with variable degrees of opening are optimum for consultation and display, but sometimes this is not possible.

I based this box/cradle on one I saw in Montefiascone, Italy, this past summer and it was made by Nicholas Hadgraft. His version used velcro to attach the left wedge into the outer tray, but after some experimentation I changed this. The basic idea, of hinging the cradle platform near the spine was his, I think. I’ve also heard about a version that automatically raises the cradle, but haven’t seen one yet– I’d be happy to add an image or diagram to this post if anyone has one to share. After thinking, experimenting and making various models, I reached the point where further simplifications created more complications. I’m sure there are many variations and hope there are potential improvements.

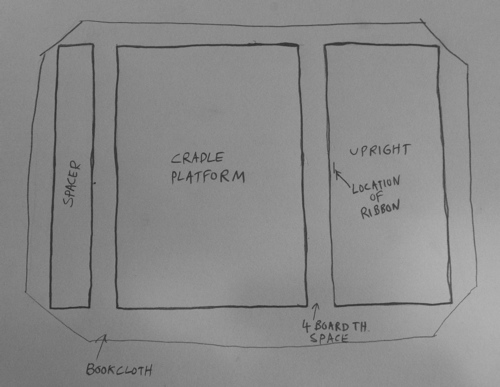

Fig 2: Diagram of the layout for a wedge.

The construction is easy and straightforward. Basically, the two wedges are made, attached together, then measured with the book to determine the dimensions of the inner tray. After that, the box is constructed as usual. The construction of drop spine boxes is well documented, so there is no reason to repeat it here.

First, determine the angle of the desired opening for the book. Then cut the three pieces of board- a spacer, the cradle platform and the upright. The width of the upright will determine the angle of the cradle. A hinge spacing of four board thicknesses worked well with Iris cloth, but a thicker cloth might need additional space. When measuring the book, I feel a somewhat “loose” box prevents abrasion of the book edges, when inserting and removing the book, which I feel causes more damage than if the book moves a few mm inside the box. About one centimeter is a reasonable gap between the spacer and the upright when it is folded flat– it allows for some flexibility in construction, yet adequately supports the book when it is stored. Then the three pieces are covered like a case binding, and lined.

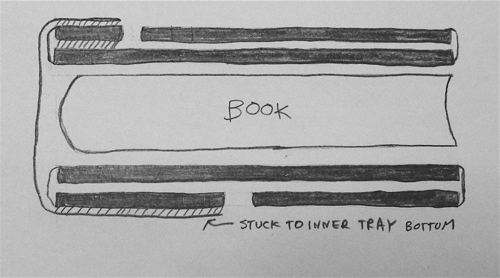

Fig. 3: End view of the book and two wedges, ready to be measured for the tray.

Another important consideration is to add about one spine thickness to the height of the upright in the outer tray, in order to keep the overall angle of each wedge roughly similar to each other. Since the book could eventually be used in a wide variety of page openings, it seemed reasonable to keep the angle of the uprights roughly even.

The wedges were attached to each other by a double layer of book cloth, glued back to back. A variety of materials seem to work for lining the platform depending on the fragility of the book covering material– I’ve used paper, cloth, volara and polyester felt. The trays need to be lined before they are measured with the book. It is possible to construct the wedges and spine piece from one piece of cloth, but measuring for a proper fit is fairly difficult and more time consuming, and then the spacers need to be made from separate pieces of cloth.

Note that on the right side wedge, the spacer is glued to the bottom on the inner tray. This allows the wedge to open, and his prevents the cradle from shifting and collapsing when it is open. The spacer on the left wedge is glued to the bottom of the cradle platform. This allows it to open independently from the drop spine box, consequently the spine width is closer to the ideal than if the wedges are hinged to the trays.

Fig. 4: View of the cradle when opening the box.

I try to make the cradle platform fit fairly tight in the inner tray, so that its friction can be used to create slight compression on the book.

One potential drawback is that it effectively doubles the thickness of a standard drop spine box, adding an additional 4 board thicknesses, plus lining materials, but presumably this is more of a concern for institutional, verses private collections.

Fig. 5: The box and cradle open, but the uprights not yet raised.

The location of the pull ribbon is quite important, and unfortunately there is no ideal solution. If it is placed about halfway up in the height, it makes it easy to pull it to 0pen the upright. But in this position, it can slip under the platform when closed. If the ribbon slips under the right wedge, it can be very difficult to retrieve (DAMHIKT). For now, locating this closer to the top, or to keep it from slipping by sewing through the hinge, as illustrated here, seem the best solution.

I trust that Peter Waters would have considered this box as an “exception” to his rule #7, otherwise I plead guilty as charged.

Fig 6: Competed box with integral cradle in position.