Clark, Adam. Christian Theology. New York: T. Mason and G. Lane, 1837.

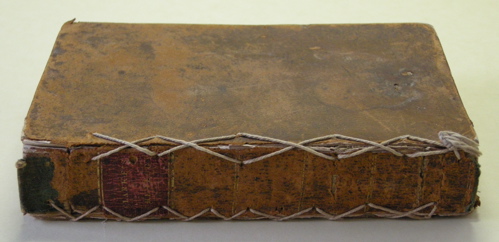

I always enjoy examining these 19th C. (or early 20th C.) book repairs where the board is sewn to the spine. This example is fairly crude, but some can actually function fairly well. This book is in my collection– I will preserve it as evidence of the history of book repair. We might find this repair laughable, but it is fairly easily reversed, there is no glue to remove and it kept the boards from getting lost. When the holes in the spine are staggered through a number of signatures, these repairs hold up fairly well, and if the paper drapes well and the spine is fairly flat, as in this example, all of the text is easily readable.

This example is missing the title page and first 14 pages, but I think it is some kind of Catholic devotional book. It is bound in typical early to mid 19th C. style and is quite small– 84 x 57 x 34 mm. Of course, I am not advocating this as a type of repair a conservator would do today, but to me it represents a 19th C. common sense approach to the most common failure in book structure– detached boards. This type of repair, fairly common in the US, might have served as impetus for joint tacketing or a literal “sewn-boards” binding. The upper board and lower board are sewn differently, the lower board like the previous example, but in the case of the upper board, the stitch runs into the edge of the board, which results in a decent opening. The brown thread which matches the calf covering is doubled like sewing thread is. Could this this have been done by a woman, and the previous “heavy duty” example done by a man?

I have hypothesized elsewhere that there might be some kind of connection between early board attachments such as in the Book or Armagh, Romanesque lacing paths, and board slotting. The spine edge of a book board is a very tempting entry point in establishing mechanical attachment. The strength, and relative noninvasiveness of board edge attachments make it an appealing treatment option, alleviating the need for disruptive lifting of covering materials. I have been experimenting with a new jig, pictured above, which holds a foredom drill at a precise angle, and has a depth stop, to accurately drill with wire gage drill bits, in order to drill a hole exactly the size of the thread used to reattach the board.

Advertisement from Science and Mechanics, Vol. XVII, No. 6, 1946, p. 38.

By the mid 20th C., detached boards and other types of damage are more commonly fixed by tapes and adhesives, as the advertisement above suggests. Unfortunately, I think I have seen this used on books. It ends up looking like a thick, completely inflexible amber mass of goop. I think this glue is the kind I used to use as a kid when assembling plastic or balsa wood models. The cap of this tube is unusual- it looks like a twisted loop of wire, perhaps used to pierce the top when opening? Often the spine edge of the detached board is glued to the flyleaf to “fix” a detached board.

By the early 21st C.,in the general public, most ideas of repairing an object mechanically are gone, and most ideas of repairing an object by using adhesives are gone. In fact, the idea of repair is almost gone. We simply buy a new one, unless the book has some kind of exceptional value.

The idea of a world where nothing is worn, nothing is fixed and everything is new frightens me. How would one conserve an ebook reader? I’m sure books will exist for a very long time, but more as symbolic representations of learning and knowledge, not primarily as a source for accessing a text. This is why these primitive, vernacular repairs are so important for understanding a previous culture’s relationship to the books they used, treasured, repaired and read.