Annie Ujifusa, who developed this variant of a cradle box, guest blogs about her process and details the construction. I came up with the one-piece cradle box in 2009.

During a book conservation internship at the Boston Public Library (BPL) last summer, I was shown a beautiful medieval manuscript from the rare books vault that was housed in a clamshell box with a delightful built-in cradle. This enabled the book to be safely opened and read without even having to take it out of the box. I was charmed by the idea and when I asked how I could make one, I was pointed in the direction of Jeff Peachey’s blog, and then I went down a rabbit hole into making and experimenting with it. I started modifying small elements until I eventually ended up with a structure that I think serves a specific, useful purpose. I recommend reading his blog first to understand his terminology that I have adopted here.

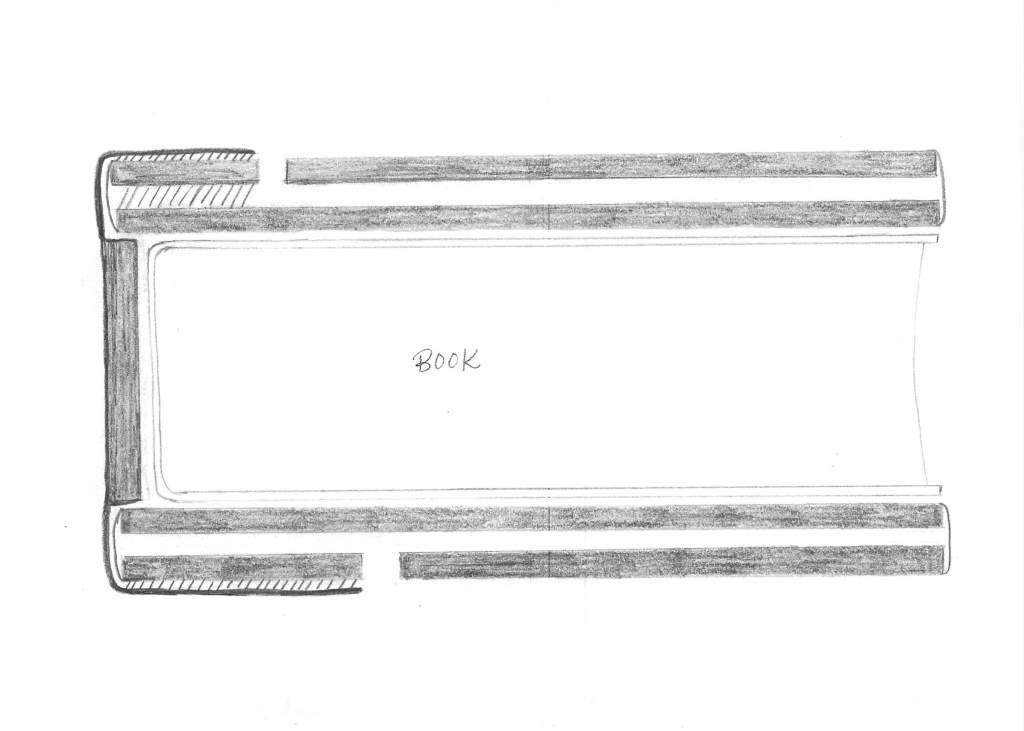

The original construction from Peachey calls for two pieces of bookcloth glued back-to-back serving as the hinge connecting the two wedges of the cradle. I made two boxes this way, and I really loved how, when closed, this limp hinge is able to wrap perfectly around the curve of the spine of the book. But I wanted to keep playing around. For my third attempt I got to thinking about what changes could benefit the structure. I wanted the hinge to have a more finished look; I decided to add a piece of binder’s board to it, making it stiff, so that the cradle looked like a complete, cohesive structure — almost like a book itself — instead of two wedges connected. A structure I was shown by Mary Hamilton French, the Conservation Officer at the BPL, came to mind as the perfect inspiration: the post binding. I took the spine from this binding and adapted it to this purpose.

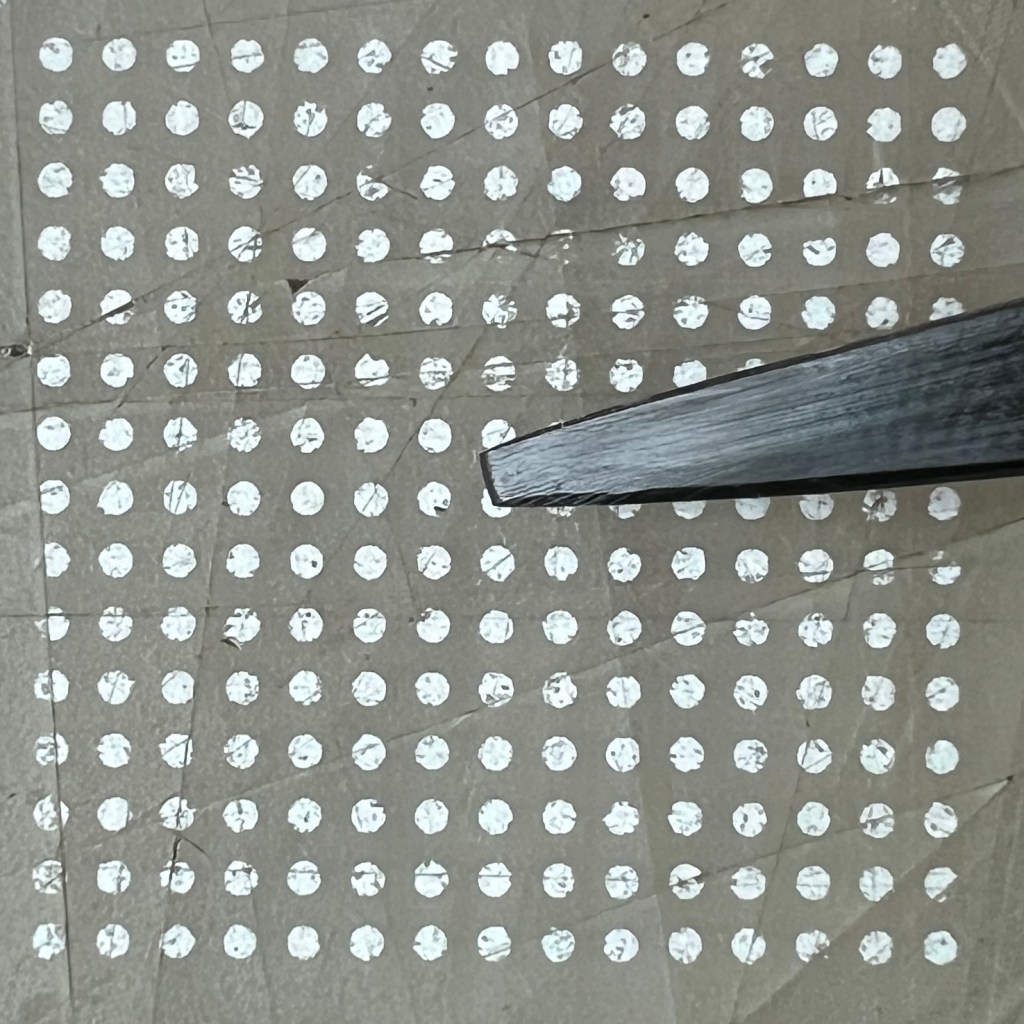

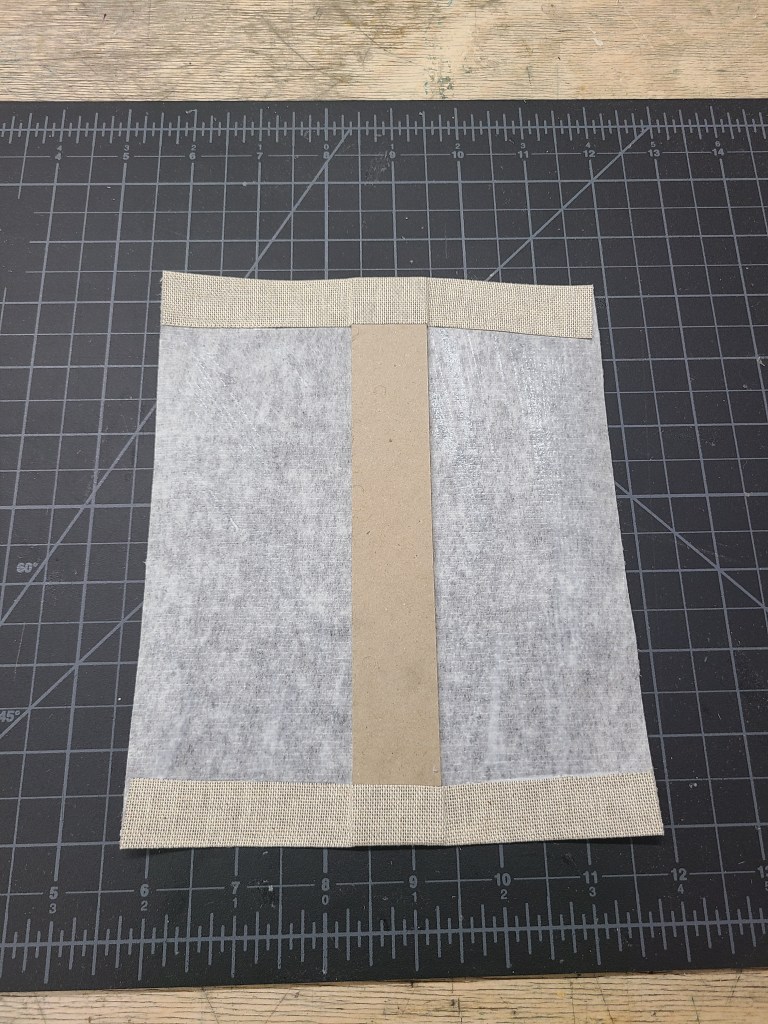

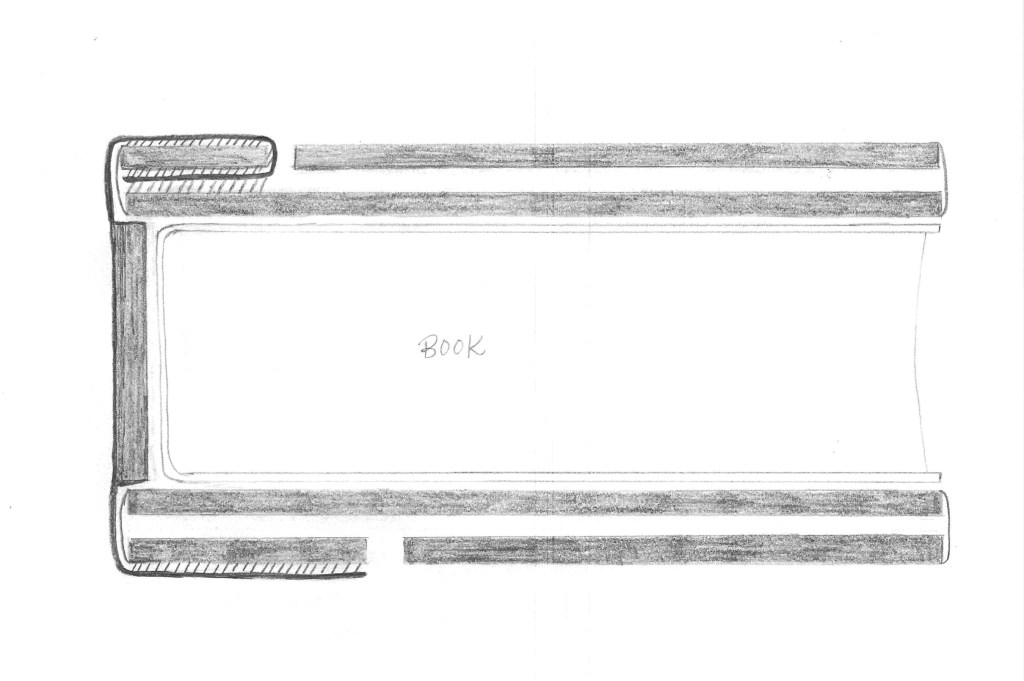

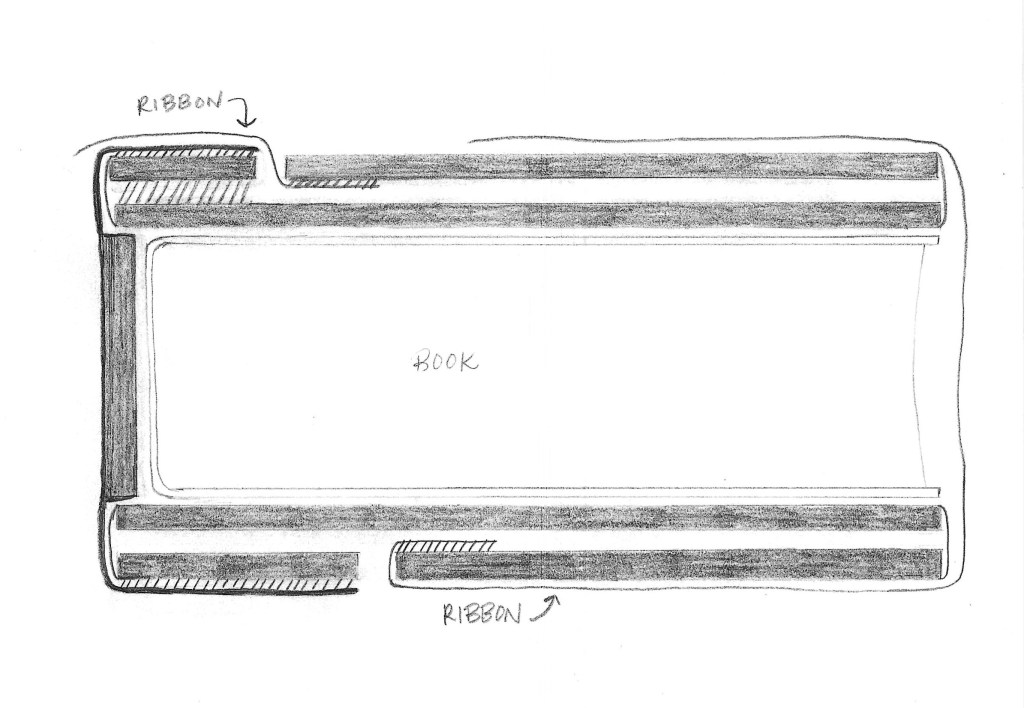

Figs 1. A: The spine piece exterior covered. B: The inside. C: .

Its construction is simple. To make it, cut the binder’s board to match the thickness and height of the book. Cut two pieces of cloth—one should have a height that allows for turn-ins around the head and tail of the board, and the other should have a height that is just a few millimeters shorter than the board. The width should be oversized for now, allowing enough to cover the spacer boards on each wedge, and then some. Glue out the taller of the two pieces of cloth and lay the board down in the center. Turn in the cloth at the head and the tail, and crease it against the sides of the board, keeping the turn-in folds as perpendicular to the board as possible. (Fig. 1A) Then glue out the other piece of cloth, lay it onto the board, then crease it against the sides and then across the expanse of the other piece of cloth (Fig. 1B) Fold both layers of cloth in, against the board edges (Fig. 1C).

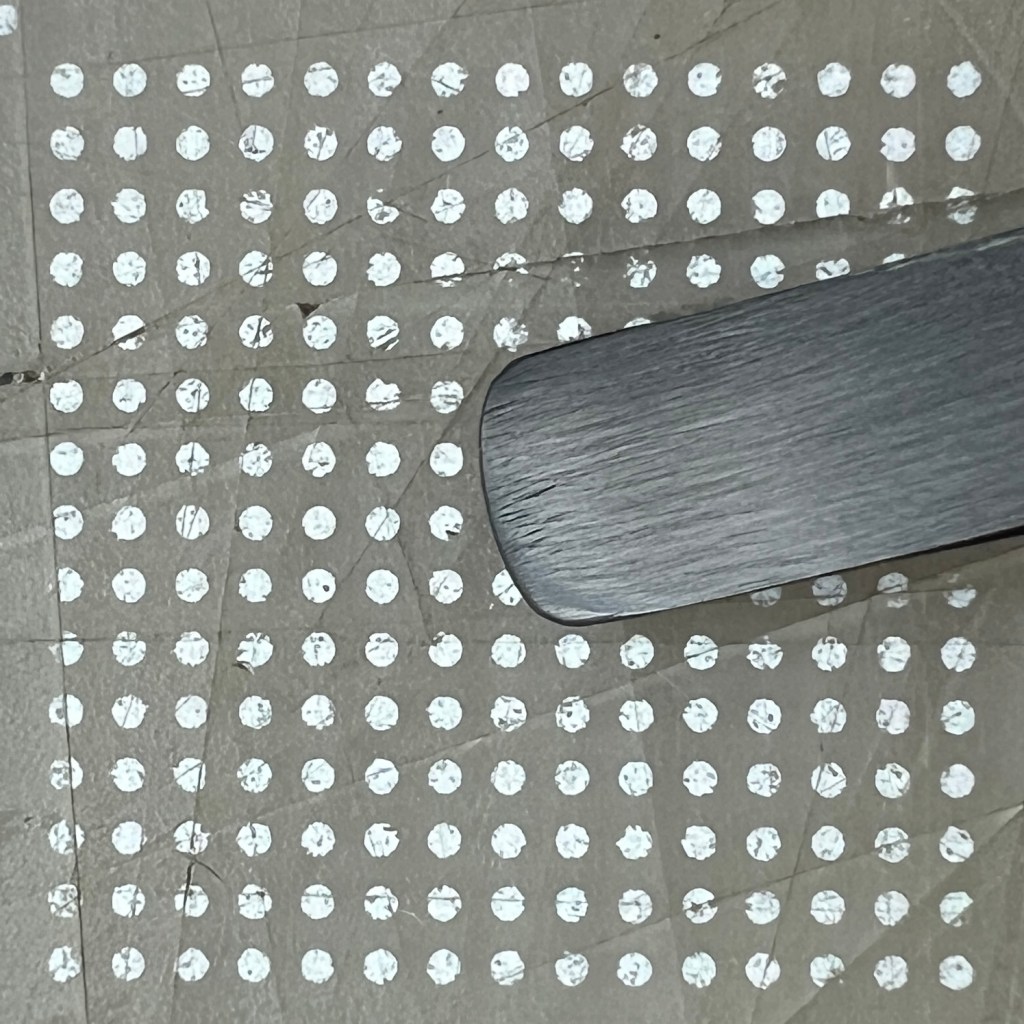

Then trim off the excess cloth. With fixtures holding the book and the folded-up wedges in place, glue one side of the hinge to the inner spacer, and then the other side to the outer spacer. If you’re using cloth that cuts nicely, without frayed edges, you can simply cut and glue the cloth down right up to the edge of the outer spacer. (Fig. 2A) Otherwise, before adhering the spacer to the platform, leave enough cloth to wrap around the spacer and glue it to the underside for a nice, seamless look as seen in Fig 2B below..

Left: Fig. 2A. A cut spine wrapper. Right: Fig 2B. At the top, the cloth is wrapped around for a more finished look.

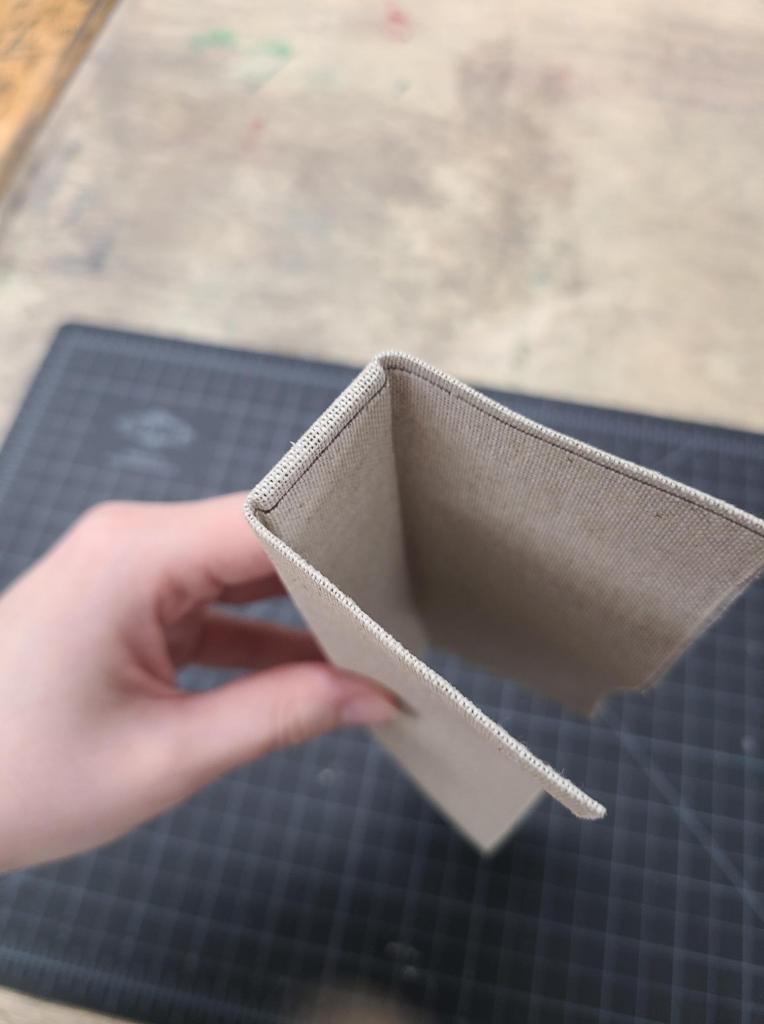

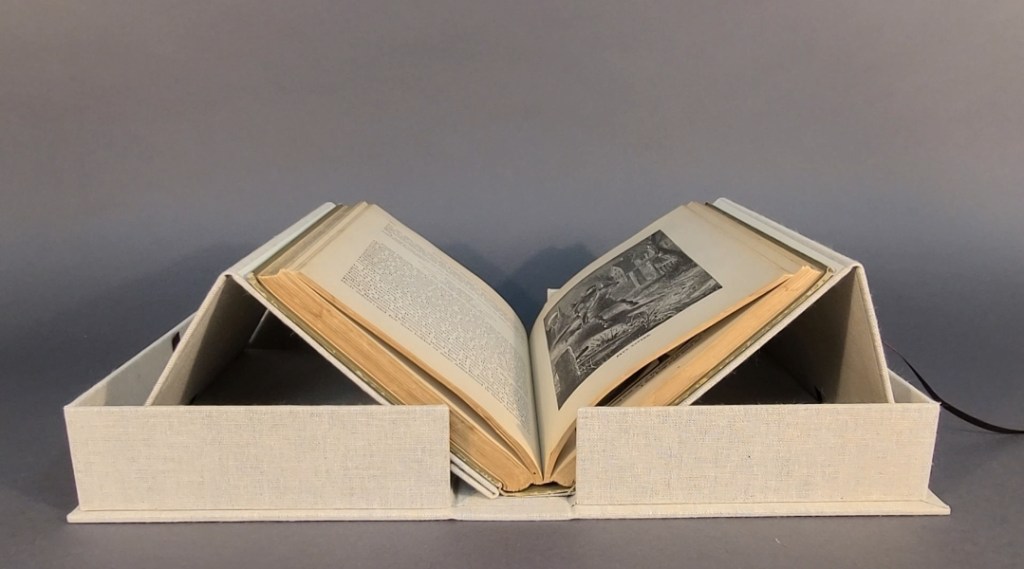

There were a couple of other minor adjustments I made. The gap between the spacer and upright was suggested to be one centimeter. I ended up reducing that to 5mm, for no other reason than I felt it simply looked more elegant. I also found that adding about one spine thickness to the height of the outer upright, as suggested, caused the wedge angle to be too steep. Instead, adding only about one third to one half of the width of the spine created an angle that more closely matched that of the other wedge. (Figs. 3A and 3B)

Figs. 3A and 3B. The left image has about a third the width of the spine added for even wedge height.

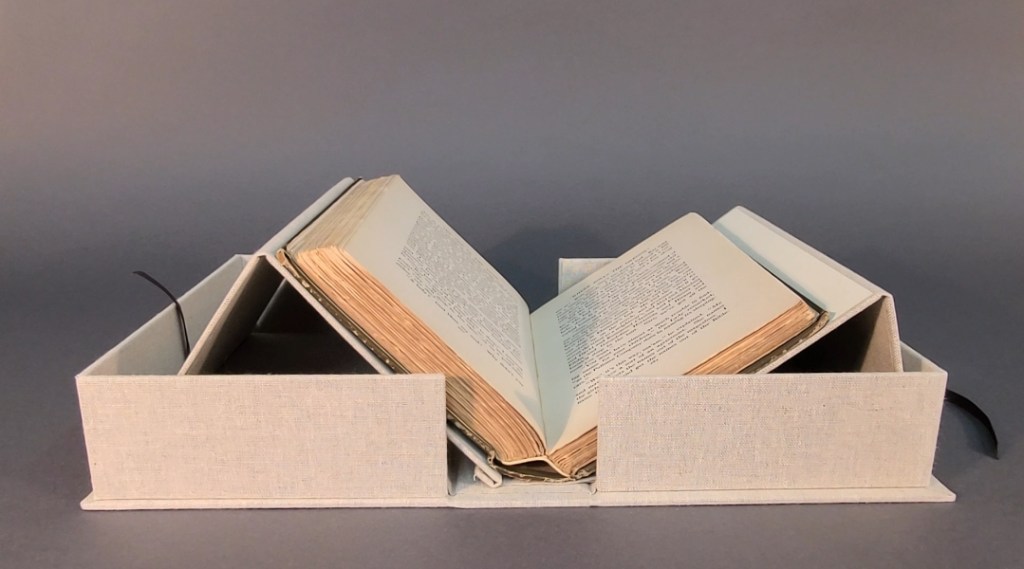

I then added the pull ribbons to a different spot as seen in Fig. 4. I adhered them to the back of the upright pieces before covering the back of the wedges in cloth. The outer wedge ribbon needs to be long enough so that it falls over the wall of the outer tray when opened, and the inner wedge ribbon needs to be long enough to span the width of the upright, the wall height of the inner tray and about two thirds of the width. I felt this saved time, while still allowing the opening to be effortless with a minimal learning curve.

Fig. 4. Ribbon placement for ease of opening the cradle.

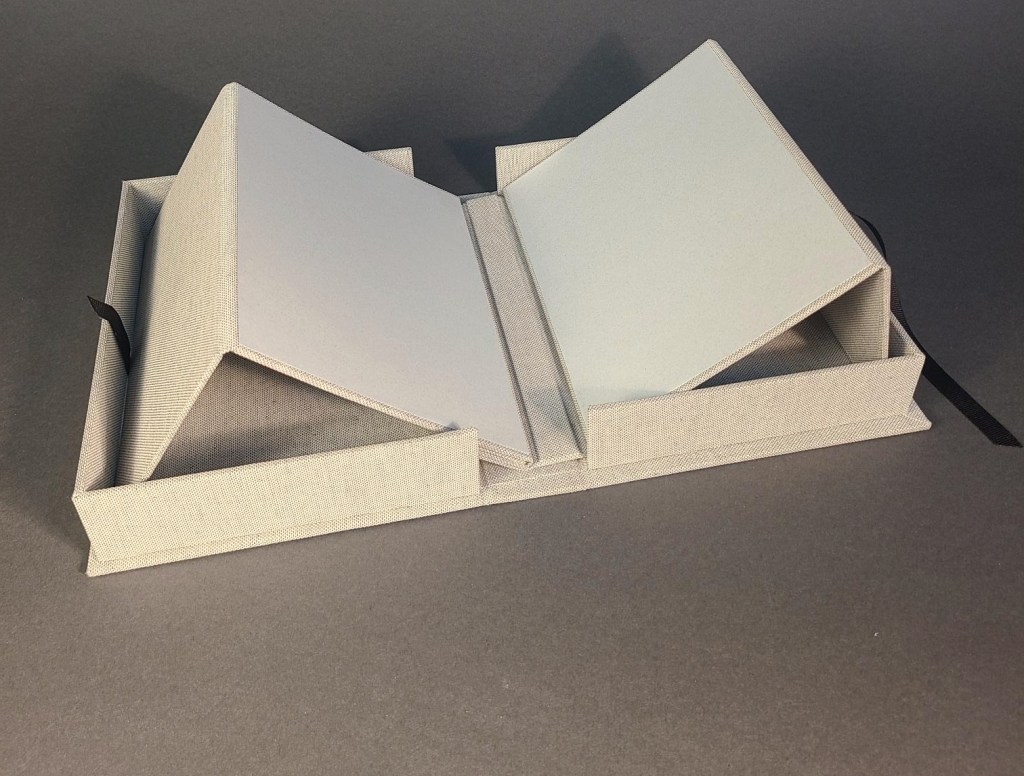

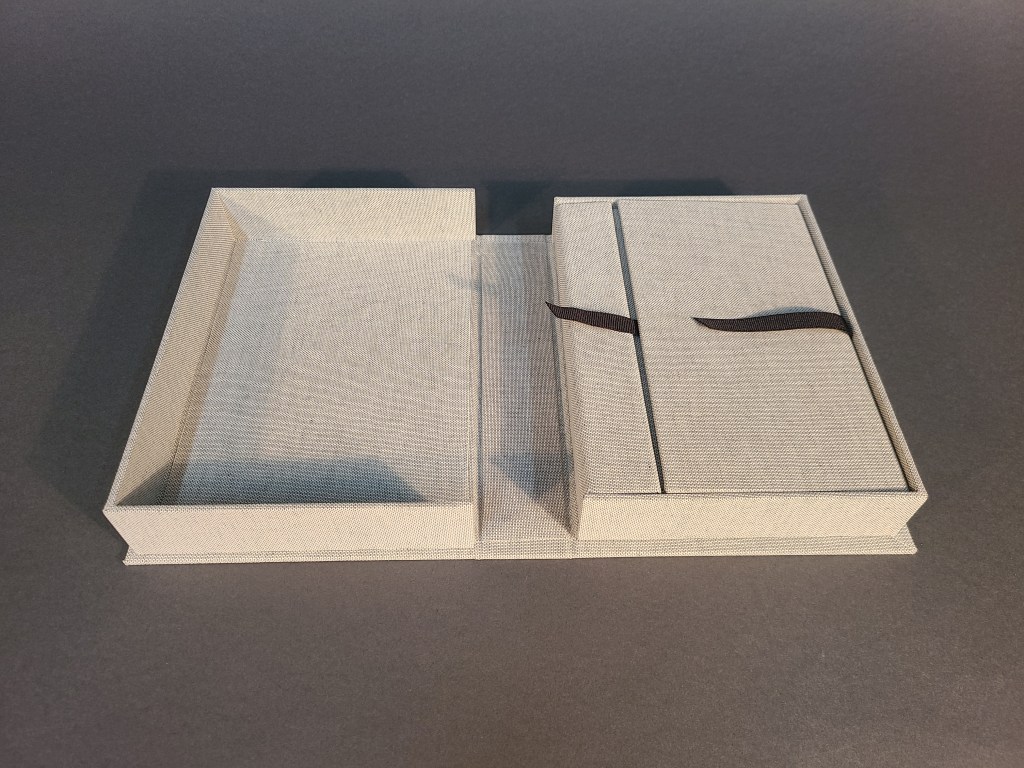

Since this was just a model, I made it for a small, skinny book (Fig. 5). At the time, I didn’t realize it’s most valuable use and greatest potential; I think it would really shine in the case of large, flat-backed books that need the added support. It’s an overall neater look in the box, and it feels sturdier when opening. It also avoids potential abrasion from the edge of the inner tray where the spine in the limp hinge would have rested on.

Fig. 5. Completed box closed.

As Peachey laid out in his blog, this type of box requires very specific needs, and has some obvious drawbacks. This one I created calls for even more specific needs, but I think that’s one of the joys of conservation. Each book and each treatment is different and has its own set of obstacles. In addition to providing protection during storage and use, this box is a sure crowd pleaser and fun to open. It was an immensely satisfying structure to make, and I’m looking forward to making more in the future!

Annie Ujifusa Bio I’m currently a second-year student in North Bennet Street School’s (NBSS) Bookbinding program. Originally from Washington state, I moved to Boston from Alabama. During my first year at NBSS, I quickly became enamored with conservation. It’s truly magical to me. I will be starting as the newest Conservation Technician in the Conservation Lab in Special Collections at the Boston Public Library after I graduate. I believe the book is an object that should be engaged with, and I can’t wait to repair and stabilize books every day so they can be safely handled and studied for generations to come. In my spare time, I hope to continue making new bindings, as well as slowly mastering the art of gold tooling, which I have become obsessed with. I’ll be trying to build my hand tool collection for the rest of my life! Instagram: @annieuji

Thanks for the great idea and post, Annie! Some other cradle boxes from around the web are here. The AIC wiki is also useful for more information.