“The ebook reader is devil spawn, the product of an unholy union between book and machine.”

Jeff Peachey–July, 2009

Last week, in a stark reversal of previously held convictions, I purchased a kindle 2 ebook reader.

Initially inspired by a number of upcoming talks I will be giving concerning the future of books and conservation, I have been reading and thinking about ebook readers for a while, especially in terms of how they might augment, change or supplant paper books. This machine is emblematic of the societal changes regarding the distribution, consumption and value of books. It can also evoke ire in those who are firmly enamored with paper books.

So I am slightly ashamed, after wrestling with the dilemma to purchase one or not for a few months, that I realized, with an intensity almost religious in its conviction, that I wanted one– immediately. Purely in the interests of research, I told myself. Last Monday, at 9:17 am I logged on to Amazon and purchased one. I’m even more embarrassed to admit I succumbed to the same day delivery option for Manhattan. Who in their right mind would wait 5-9 days for free delivery, I reasoned. I wanted this machine now. During the day, I was embarrassed yet again, by how excited and eager I was to get my kindle. At 2:26 that afternoon the machine arrived.

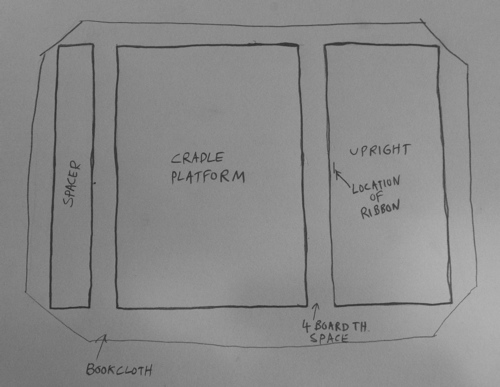

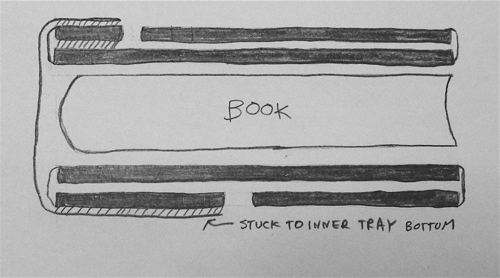

After charging the battery, my first thought was to make some sort of case to hide protect it. This proved more challenging than initially envisioned. A number of designers and computer case makers have fabricated various holders, hinged book-like portfolios and envelopes, but none of these seemed satisfactory, since I found the machine very comfortable when held naked. I ended up making a slipcase lined with Volara, which works for now.

The next step was to inform some of my friends and colleagues that I had bought this reading machine. Not surprisingly, I received a variety of responses, ranging from “WHAT!” to “WHAT THE…!” to “ARE YOU CRAZY?!!” to “OH_MY_GOD!” After downloading a number of free books, I settled on my first purchase; “Erewhon”, by Samuel Butler. It is a novel describing a future civilization that only has knowledge of machines through reading about them in books.

I must confess that I like the kindle, but have only used it for a week.

THE BAD

*It is another expensive portable electronic device that I have to remember to recharge.

*I keep wanting to scroll, but the machine can only turn pages.

*The page turns are much faster than earlier versions, but still pretty slow, and still accompanied by a split second seizure inducing reversal of text and background.

*ebooks themselves seem overpriced to me- around $10. Since there is no production, distribution and minimal storage costs, $5-$7 would seem more in line with the profit margin on paper books.

*There is no secondary marketplace for ebooks.

*Rapidly “flipping” through to find specific pages is difficult.

*It is strange to read everything in the same font- Caelicia.

*It is strange to read everything on the same “page”.

*The formatting and kerning are quite variable and often very bad.

*The footnotes on the books I have are not in hypertext, so it is awkward to first go back to the table of contents, then to the notes, then page through each to find it.

*The 6 inch screen seems small in relation to the size of the machine. Not that many words-per-page even with a small font size.

*I still find the machine itself a little distracting to the reading process. Maybe it is just a matter of me getting used to it. It invites me to fiddle with buttons and check the web.

*Occasionally the screen glares in a strong light source.

*The “text to speech” voice is annoying and virtually unlistenable.

*I wish the background of the screen were a little whiter.

*Many books and journals are not available.

*I don’t like the idea of an ebook readers.

THE GOOD

*It seems well made, the buttons have a nice inward click. Easy to hold with one or two hands. Good ergonomics.

*Lighter than an average book of the same size. And obviously, much lighter than 1,500 books.

*Purchased books are backed up by Amazon, and can be shared on other formats, like the iphone or computer. Even bookmarks and notes are shared.

*It is very convenient not have to think about what book to take when I go out.

*The choice of five font sizes is invaluable for the over 40 crowd.

*It is fantastic to use while eating, lying flat, taking up half the table space of a paper book.

*The eink is clear and easy to look at for long periods of time. Better “print” quality than many common mass market paperbacks.

*There are thousands of free, public domain books available.

*It it a wonderful size for reading in the car or on the subway. It is very easy to turn the pages on a packed train while standing.

*The battery life is great. I’ve used it constantly for a week, and haven’t turned it off, only recharging it once.

*The free 3G web browser works reasonably well for mobile optimized websites.

*It will help clear up scarce bookshelf space.

*An average book downloads in less than a minute.

*I imagine it will be perfect when traveling- no worries about running out of books, and a lot less weight.

I will avoid the already somewhat tiresome “is the kindle better than a book” debate for now, at least until I’ve had a couple of months to use it. Suffice to say, there are many issues. But the ebook reader itself may already be heading towards obsolescence. A couple of ebook blogers are nervous that the tablet computer, which Apple will possibly introduce later this week, may replace their traditional ebook reader, and are growing anxious and defensive about it. Technology races onward.