Scott W. Devine

In 2015, I taught a course on 16th century Italian slotted parchment bindings for the Montefiascone Project Summer School. I was excited to be a part of the program that year, which celebrated 25 years of teaching conservation and bookbinding at the Seminario Barbarigo. The process of designing the course and being involved in a subsequent research project provided insights into the value of recreating historical book structures.

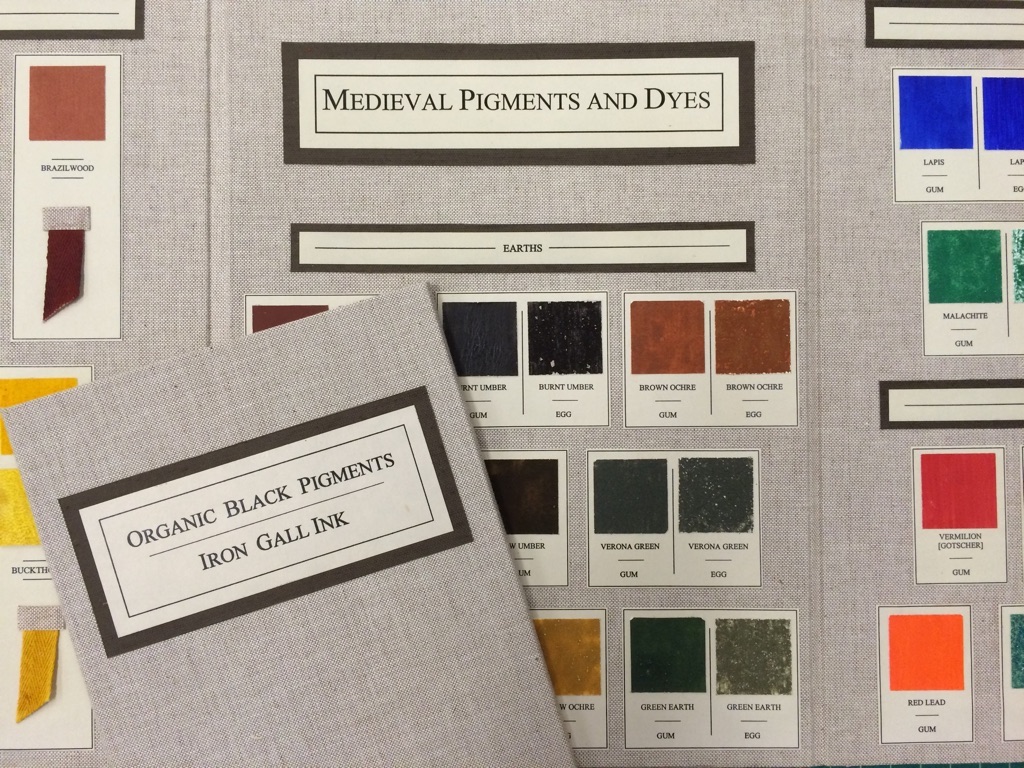

I attended my first course at Montefiascone in 1998. Having recently completed an internship at the Library of Congress, which included working on a pigment consolidation project for a collection of illuminated manuscripts, I was eager to learn more about the techniques used to create these manuscripts, and Cheryl Porter’s course on “Re-creating the Medieval Palette” represented an ideal combination of lecture and hands-on practice. The process of grinding minerals and boiling organic matter to create a range of color opened my eyes to the incredible value of recreating historical processes: understanding how an object was created through practicing historical techniques can lead to unique insights into how to go about conserving that object. In this sense, learning how to recreate historical processes and techniques becomes a fundamental aspect of training and professional development for a conservator.

Over the past 30 years, the Montefiascone Project has developed into a well-established international training ground for conservators, bookbinders and scholars: a unique place to explore bookbinding technique, book history and conservation issues in a collaborative and creative environment. The book program in particular has developed into one of the best ways to study historical structures, often in the context of a specific bookbinding selected from some of the premier rare book collections in the world.

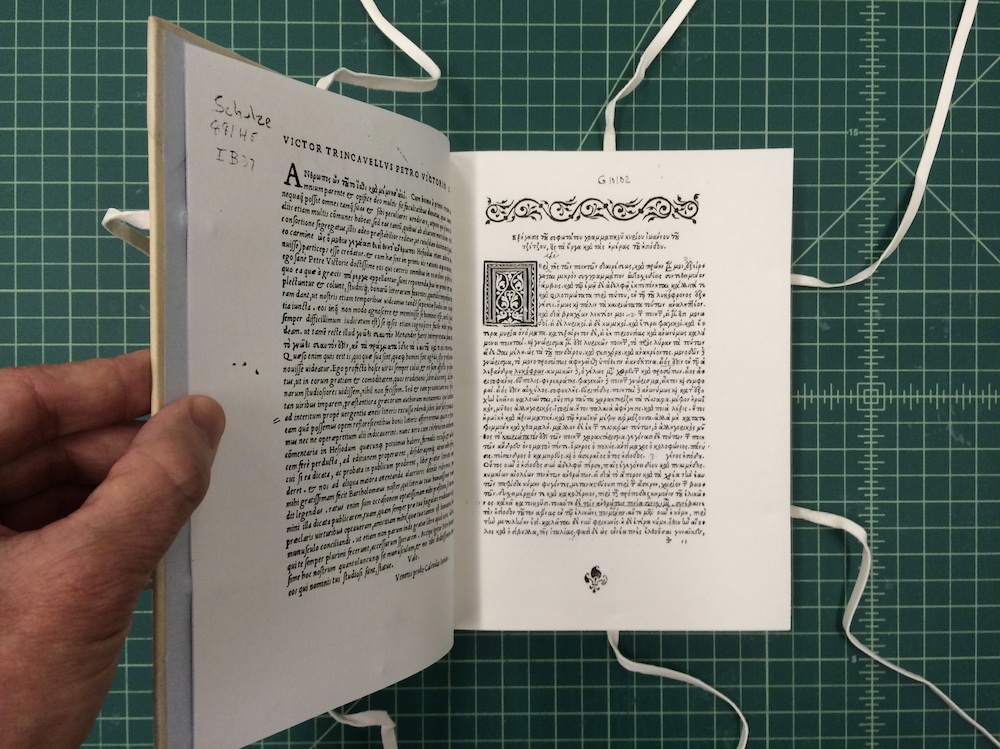

I taught the slotted parchment structure using a copy of Hesiodou tou Askraiou Erga kai hemerai (the Greek poet Hesiod’s Works and Days), printed by Bartolomeo Zanetti in Venice in 1537 and currently held by Northwestern University Library. The printed text is derived from a 15th century Greek manuscript held by the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice. In preparing the course, I started thinking about the larger issues surrounding why we study historical book structures and why the construction of historical models is so critical to the study of book conservation.

1. Developing and refining conservation skills.

Constructing historical models allows the conservator to develop bookbinding and conservation skills in a way that treatment alone does not. While most book conservators have studied traditional bookbinding techniques, such as covering with leather or constructing brass clasps, these skills are infrequently required in modern book conservation and are all too often lost. Maintaining these skills allows us to use them when needed and appropriate. More importantly, however, the continued refinement of these traditional skills allows us to spot variations in technique on the historic bindings we handle. Being able to distinguish variations can assist in dating or identifying the region of creation and lead to further insights into the spread of bookbinding technique.

On a more personal level for the conservator, constructing a book from the beginning allows for a free expression of intent not always possible in conservation treatment. Conservation has always been an exercise in compromise and balance: artifactual value, curatorial needs, and the changing political and cultural norms that guide our work. At a time when so much of our work is driven by external factors beyond collections care – digitization initiatives and exhibition schedules chief among them – having the time to get lost in the details of a specific book, if only for week, can be both invigorating and rejuvenating.

2. Gaining insight into historical techniques.

There are two common approaches to recreating historical book structures: 1) constructing a facsimile binding which combines aspects of the most typical examples of the structure being studied; and 2) recreating a specific book. Both methods allow for the development of the hand skills discussed above. However, the latter approach allows us to look more closely into the physical aspects of a specific object, often requiring a higher degree of attention to detail in order to make the facsimile function in the same way.

The process of reproducing a specific binding often challenges our assumptions about how the object was created in the first place and invites us to investigate specific components in detail. In the case of the Northwestern Hesiod, trying to achieve specific results led to a greater understanding of how the book was produced, including how the pasteboards were constructed and how the covering vellum was processed.

We often look at an object and think we know how it was created, but until we try to replicate the technique, we don’t really know. With the Northwestern Hesiod, I conducted numerous experiments to create a modern pasteboard that mimicked the weight, feel and function of the original. The process of making these sample boards led to a better understanding of the role of the pasteboard in controlling the movement of the covering vellum. As a result, one component of the course focused on creating pasteboards with Fabriano CMF Ingress (Bright White) 90 gsm paper. Each board consisted of 17 layers with alternating grain direction, beginning and ending with the grain parallel to the spine of the book. The layers were attached with thick wheat starch paste and pressed briefly in a book press to remove excess paste. Air drying was essential, and if the layers started to delaminate, they were placed briefly back in the book press. The resulting board was lightweight but surprisingly rigid and strong enough to counter the tension of the vellum covering material.

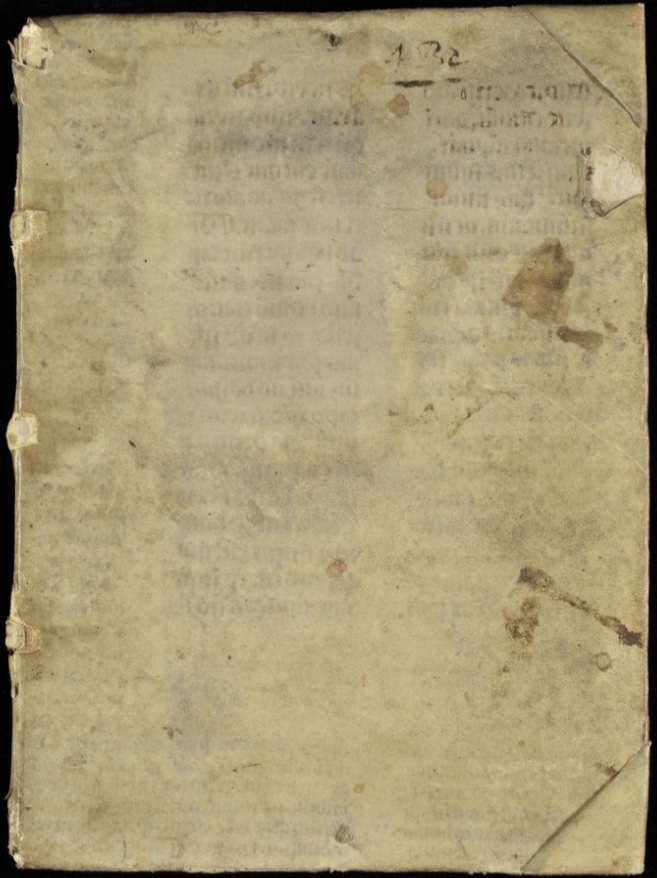

The vellum also posed a challenge. Careful study of the covering vellum, a recycled 15th century manuscript heavy scraped and sanded on one side to remove the original text, led to collaboration with Jesse Meyer at Pergamena to custom produce remarkably thin vellum for the project. Various experiments in covering with the thin, unlined vellum resulted in new skills and techniques which were put to good use during a subsequent parchment binding repair project at The New York Academy of Medicine in 2018.

3. Engaging in scholarly research.

In preparing the course on the Northwestern Hesiod, I had the opportunity to engage in traditional scholarly research in a way that is not typical of most conservation treatments. My research with the Hesiod began as an effort to understand more about the slotted parchment structure and to quantify holdings in North American research libraries. The goal was to build on the research begun by Silvia Pugliese and, specifically, to determine the prevalence of slotted parchment bindings in collections outside Italy.1

In the process of studying slotted parchment bindings, however, my interest developed into learning more about Bartolomeo Zanetti and the other books he printed during his time in Venice. I became particularly interested in how these volumes fit into the larger economic and social context of the period, especially the rise of Protestantism and the effect of the Catholic Counter-Reformation on the Venetian book trade.

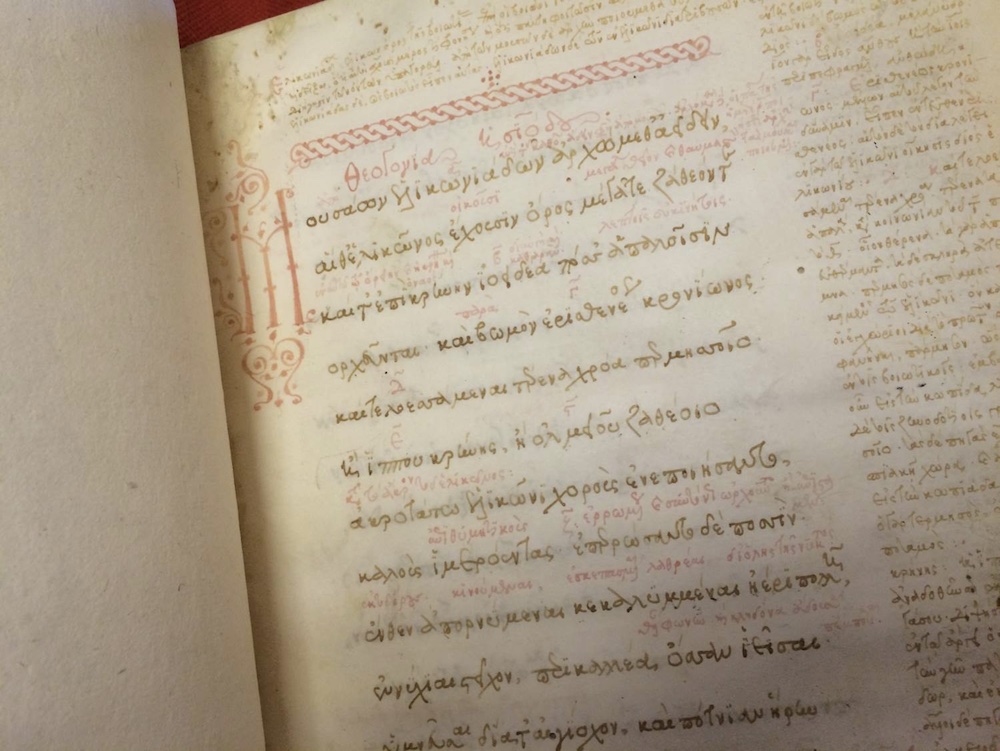

During a research trip to Venice, I had the opportunity to study the 15th century manuscript by Demetrio Damilas, Marc. Gr. IX 6 (coll.1006), which Zanetti used to create the 1537 Hesiod. In fact, the 1537 Hesiod is notable for the extensive scholia, or notes, which were copied from the Marciana manuscript. Zanetti’s efforts to edit and reproduce the scholia are remarkable. The way in which the printed book reflects the original manuscript is a fascinating case study in the intersection between manuscript and print culture and represents another aspect of research which will be discussed in the course.

Having the opportunity to engage in this level of scholarly research is important for the conservator. Understanding how individual objects are used by researchers, putting ourselves in the role of those researchers, helps inform the decisions we make about preserving artifactual value and makes us more aware of ways in which our collections are being used by scholars.

4. Collaborating with colleagues in other fields.

My interest in the Northwestern Hesiod led me to make connections with experts in the fields of both Renaissance Studies and Classical Studies. Learning more about Hesiod and Greek scholarship in the Renaissance has led me to a better understanding of why so many books were being printed in Greek in the early 16th century and the role of Greek language in the development of Italian Humanism. Learning more about the efforts of 14th century scholars such as Giovanni Boccaccio and Francesco Petrarca to revive the study of Greek and the importance of work by early teachers of Greek such as Manuel Chrysoloras provided new insights into how and why the Venetian book trade developed as it did in the early 16th century and why the study of Greek texts was so important at this time.

In addition, my research on the covering vellum and the recycled manuscript, which was assumed to be from the early 15th century based on paleographic analysis, led to consultation with the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, a collaborative venture between Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago. A team of conservators from Northwestern developed a project proposal and worked closely with conservation scientists and imaging specialists from the Center to design and carry out a research project to uncover the text on the manuscript.

We were particularly interested in the manuscript text as it could shed new light on the kinds of manuscripts which were being dismantled during the early 16th century. It was even possible that the extensive marginal notes on the manuscript may reveal unique commentary, even if the principal text was not unique itself. In fact, the principal text and scholia, in Latin, were identified as part of the Institutes of Justinian, an early effort to codify Roman law and a foundation for modern Western European legal systems. The marginal notes, in Greek, represent unique interpretations, adding to the scholarly study of civil law in 15th century Italy. The results of this research were published in 2017.2

My time working with the Northwestern Hesiod led me to conclude that the making of historical book models represents one of the best ways to explore firsthand the complex nature of book structure and to develop insights into conservation technique. Moreover, the study and construction of historical models represents a unique opportunity for anyone, from amateur bookbinder to experienced conservator, to experience history in a way that few people can. It reminds us of how we connect to the objects and techniques that excite and inspire our work and represents a salient reminder of why we do the work we do.

* * * * *

1 Silvia Pugliese. “Stiff-Board Vellum Binding with Slotted Spine: A Survey of a Historical Bookbinding Structure.” Papier Restaurierung: Mitteilungen der IADA. Vol. 2 (2001), 93-101. Online.

2 Emeline Pouyet, et al.“Revealing the biography of a hidden medieval manuscript using synchrotron and conventional imaging techniques,” Analytica Chimica Acta, Volume 982, (22 August 2017), 20-30. Print.

* * * * *

©2021 Scott W. Devine

An earlier version of this essay appeared as a blog post on Beyond the Book: Preservation and Conservation at Northwestern University Library on June 17, 2015. It is no longer online.

Scott W. Devine is a book and paper conservator with over twenty years of experience in the field of conservation. He holds a Masters of Information Science with an Advanced Certificate in Conservation Studies from the University of Texas at Austin and received additional training in rare book conservation at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. and at the Centro del bel libro in Ascona, Switzerland. He has established conservation programs at three major research libraries in the United States and consulted on a broad range of conservation projects throughout Europe and North America. His research interests include the history of Italian bookbinding and the politics of preservation in Italy. He has designed and taught courses for the Montefiascone Conservation Project Summer School in Italy and currently works as a paper conservator for the Smithsonian Institution.