Peter Zillig, who writes the insightful, wide ranging VUSCOR Books/ Paper/ Reused Objects/ Steampunk Blog, sent me a link to some early portraits of German craftsmen, House books of the Nuremberg 12 Brothers Foundation. (Here is a link to Zillig’s blog via Google translator, which isn’t very accurate). After analyzing the scene, Peter reflects on his own appetite for bookbinding tools, when realistically only a few are necessary. There are 9 bookbinders in all pictured, and their birth dates are from 1532-1762. There images are fascinating, and worth spending some time with, below is one I found particularly interesting. There are over 1400 portraits depicting many trades, including a beater of metal flakes, a chain mail maker, a capon feeder and a brazil wood masher. These books were digitized in 2008.

Vasare Rastonis sent me the following explanation of the project:

“The “House books of the Nuremberg 12 Brothers Foundation” Project is a study of the house books of Konrad Mendel, a wealthy merchant in the 14th century and Matthaus Landauer, a contractor of some sort in the 16th century. Konrad Mendel set up a foundation which provided food and housing for 12 poor people at a time in 1388. The books document the needy who were taken into Mendel’s, and later Landauer’s, care and taught a trade/craft. The Mendel books, in the early years, contained a portrait and the person’s birth date and name and in later years a brief biography was included.

The project is to document each book and page digitally including a photo and written description of each entry so that the crafts/trades practiced in Germany between the 15th and 19th centuries are accessible. The project partners are the Nuremberg Public Library, who possess the books, and the German National Museum, who seem to be the supporters of technological information… I am going to guess that this means that they promote the dissemination of technological developments, history and information.

In total they have documented 1430 portraits and have included information on the bindings. The website, as you noticed, has been set up in such a way that you can look at each book page by page or search by trade/profession, by a “brother’s” last name, work equipment, materials, finished products and EVEN medical condition!”

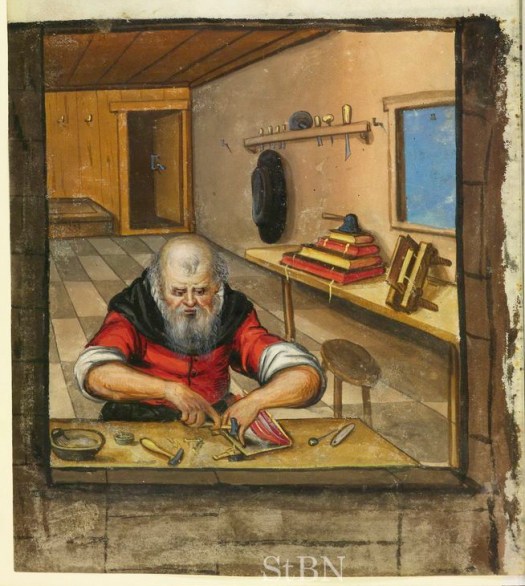

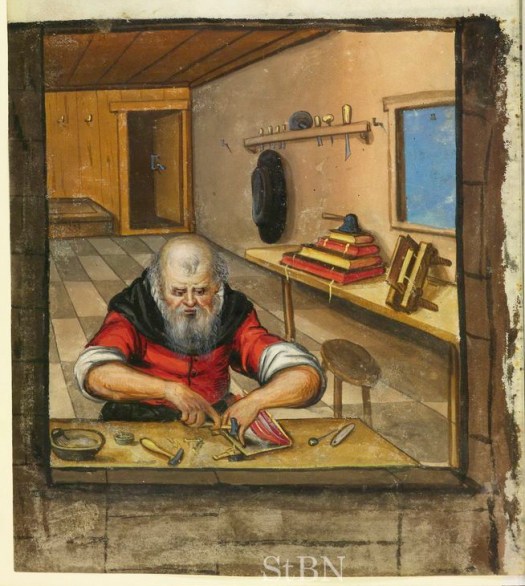

This painting is of Nicasius Florer, dated 1614. Foot simply describes his as “…portrayed at age 77, seated at a table with a bound book to which he is attaching a clasp. A folder, a hammer and a bowl and sponge are on the table.” (134)

The sharp eyes of Peter Zillig noticed a few additional items of interest, in paticular what he describes as a circular plough knife blade on the wall, a beating hammer used as a weight (btwn 5-8 kg.), a falzbein(bone folder) and a leimpottchen (pastepot?), and two hammers. He also notes the text describes a “Beitel awl” stuck into the wall. Keep in mind some of these terms came through Google translator so could be butchered.

It is endlessly fascinating, contentious and complex to attempt to identify the tools portrayed in early illustrations of bookbinders, but here it goes. Florer is labeled a bookbinder, but it seems possible that he is a clasp maker, which I thought were different trades at this time. Or perhaps he is just attaching the clasps onto the books. Note the beating hammer used as a weight, which makes me think that this was a binder, and the white, alum tawed straps awaiting their clasps. The shape of spines of these books shout out “Made in Germany”.

In comparing this with Jost Amman’s binder’s shop of 1568, there seems to be very few tools in the workshop. Of course, since this is a portrait, not a shop view, perhaps Florer chose his favorite tools to be pictured with. And if this binder was attaching clasps to the exponential flood of books that occurred in the early 17th Century, his strong looking arms may be an accurately portrayed.

The tools hanging up in the background appear to be wood carving chisels and a mallet in the center, though Zillig interprets this as a plough blade, which makes sense that this sharp tool would be stored out of the way and paring knives. But if it is a plough blade the storage seems somewhat precarious. Could the smaller tools at the other end be gravers, (Zillig calls them “gravierstichein”) which would support the hypothesis that this man was a clasp maker as well as a binder? This storage shelf must have been built especially for these tools- the blades hang between two pieces of wood (or drilled out wood) and the handles keep them from falling through. I use a similar method to store handsaws at the back of my woodworking bench. If these are chisels, they were possibly used for the shaping of the wood boards, or perhaps Zillig is right that these are paring knives. The sharply angled fishtail chisel in the front could be used for edge paring with a forward motion, like modern German paring knives. The small press, resting against the wall is a fairly standard German style with nuts, rather than handles used to tighten it. It also looks like some kind of wood board against the book in the press– used for adjusting the clasp tension?

The foreground is occupied by Florer, attaching a clasp to the leather straps and it looks like a small anvil underneath. The tools he is using are possibly a handless brush in a paste pot (is this what Foote interpreted as a sponge?), but Zellig describes this is “Leimwasser” on the left. The German word leimen means to spread with glue. small unidentified pot (containing tacks or pins?), a chasing hammer (the shape of the handle is still in use today by silversmiths) some clasps (perhaps already completed by someone else?) , a riveting hammer, an awl and a bonefolder on the right. If it is a bonefolder, this is more evidence to support the claim this man is a bookbinder. I’ve never seen a hang hole in a bone folder, however, it seems to be a Germanic tradition, Foot includes a plate from P.N. Sprengel in Kunste und Handwercke in Tabellen mit Kupfern that pictures one dating from 1778. (45) Florer is most likely sitting on a three legged stool, similar to the one behind him and there is large chest at the back of the workshop. The style of latch on the door is still in use today on primitive outbuildings in rural America. And that is one big hat–fashion statement or a symbol of social stature?

These are just a few preliminary observations, and I welcome corrections. This site is a fantastic resource for anyone interested in the history of technology and trades. The high quality, large image size make it easy to examine in detail tools from this time period. The database is easy to search, and English subject terms are provided. Some of the books that house these images appear to have been rebound and the original pages adhered to a new structure. Perhaps these books were badly damaged, but it is doubly unfortunate since there is a chance that perhaps one of the craftsmen depicted could have also been the binder.

******

Bockwitz, H.H., ‘Alte Bildnisse von Buchgewerblern und ihrer Hantierung’, Archiv fur Buchgewerbe und Gebrauchsgraphik, 75, heft 11, 1938, 419 (Abb.4), 420 (Abb. 5)

Foot, Mirjam M. Bookbinders at Work: Their Roles and Methods. The British Library and Oak Knoll Press: London and New Castle, 2006.

Sprengel P.N., Kunste und Handwercke in Tabellen mit Kupfern Berlin: 1778.