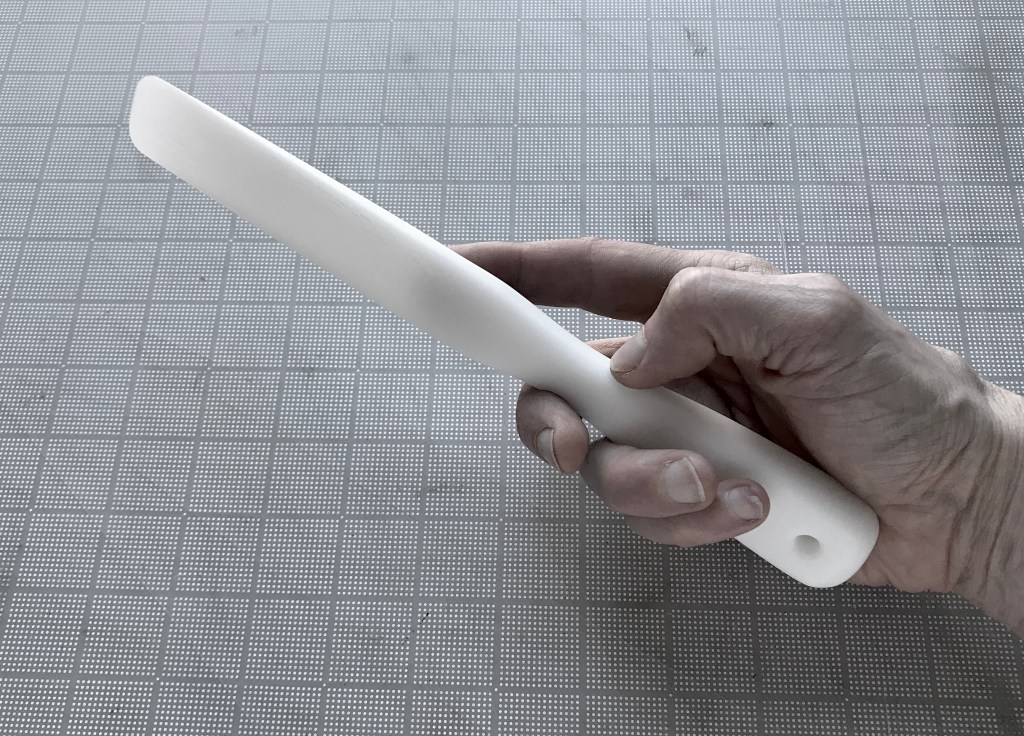

Most lifting tools are quite thin. Usually, this is great. But the thinness of the lifter results in a lack of control at the tip. In order to counteract this, I’ve come up with a very long wedge shape lifter that provides an an incredible amount of control for lifting, twisting, sliding, and prying. The straight cutting edge and rounded corners also aids precision manipulation.

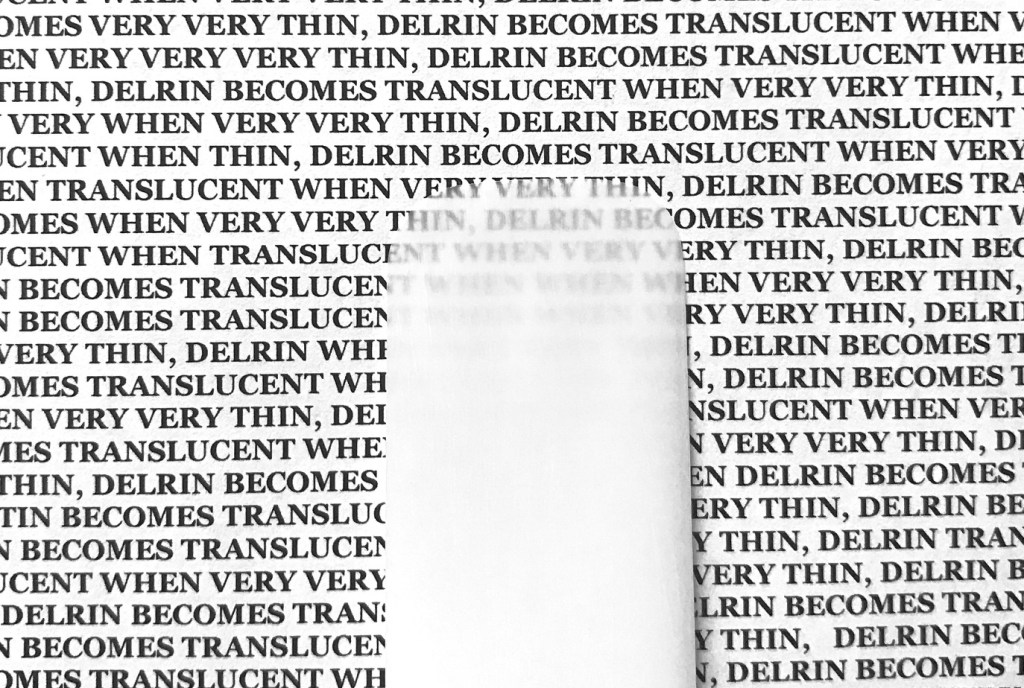

This Deluxe Delrin lifter is designed for the lifting covering materials, backing removal, hinge removal, and tape removal. The cutting edge is flexible and so thin that the white delrin becomes translucent, a feature that could be useful in certain treatments. Delrin has a very low coefficient of friction, close to Teflon. The handle is hand carved out of a bar of Delrin .75 inch thick and an inch wide. The length gradually tapers, and the weight gives this precision tool a solid heft and a tremendous amount of control.

A must for paper, book, photographic, and other conservators and restorers. The length varies between 8 – 10 inches, since it is difficult for me to get a sharp, translucent, and flexible edge. They tend to get shorter and shorter as I work on them! If the overall length is critical to you, send me a note and I will let you know what is in stock.

Between 8 — 10 x 1 x .75 (thickness at the handle) inches. Tapered gradually along the length. The cutting edge is straight with rounded edges, to facilitate twisting and prying. A basic kit for maintaining the edge with instructions is included.

The Deluxe Delrin Lifter $95.00