The celluloid paper knife below is a late 19th or early 20th century and issued as advertising from the A.N. Kellogg Newspaper Company. I’m confused about distinctions between paper knives, letter openers, page turners and even bone folders. Neither Etherington or Glaister define their differences, and a few quick internet searches seem to lead to antique dealers selling Victorian versions. So here is my first attempt at a definition: a paper knife is a large, special purpose type of bone folder, usually with a distinct handle and sharp blade. It is often made from wood, bone, ivory or celluloid. It is shaped to allow the user to rapidly slit paper folds.

The marking on the blade reads “Proprietors of Kellogg’s lists established 1865″. Kellogg’s list was a compilation of ” Family weekly newpapers of a better class” with price lists for advertising. The proprietors seem quite savvy with marketing- note the book Google scanned was donated by the publishers to Harvard College Library in 1897. The surface of the celluloid contains a grain like structure, presumably in order to resemble bone or horn. When a new material is introduced, it often contains superficial decoration to make it appear more like the original material, this is called a skeuomorph. Book structures contain many examples of these as well– artificially grained leather, stuck on endbands, fake raised bands, etc….

I didn’t want to damage the original, so I made a reasonably accurate reproduction out of Swiss pearwood. When testing the knife, one feature immediately became apparent due to the gentle curve. It is possible to use the knife to slit a fold moving towards the left, as illustrated below, or moving it forward with the top edge of the knife. It is not so comfortable for folding, if you are holding the handle, since it is so long and the edges are quite sharp, which also supports my hypothesis that this is a single purpose professional knife, and not a general purpose folder. Whoever used it must have had pre-folded sheets. Given the overall length of 12″, I wondered if it was intended as an in house distribution for the various press rooms that were part of the Kellogg empire. I am unclear why the end of the handle is so pointed– it seems potentially dangerous– did it have some special purpose, or was it supposed to resemble the end of an horn? In the original, the handle is chipped at the very tip, possibly it was used to open packages?

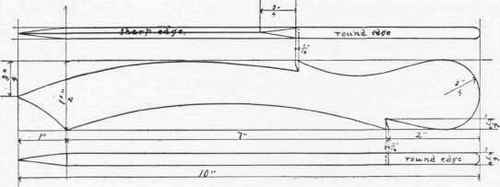

Paper knives must have been fairly popular, an introductory text for woodworking has making one as a project, although it looks rather crude and slightly dangerous, with the sharp angles.

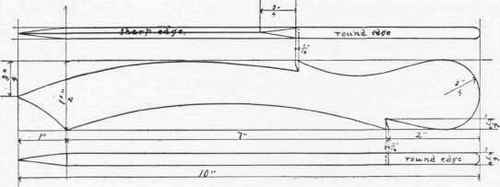

Schwartz, Everett. Sloyd Educational Trainning Manual . N.P.:Educational Publishing Company, 1893.

The rounded handle on this model seemed more comfortable than the one I made, but there are similarities in the shape of the curve and overall length and width. If I am recalling my mechanical drawing class from High School correctly, it seems the sharp edge of the knife is only on the top of the drawing, which suggests it would be used by pushing forward. The text, in six succinct sentences, describes the fabrication of this knife. I’m always impressed by the level of common sense that is presumed in 19th C. and earlier manuals, and by the familiarity with the full range of woodworking tools, from axe to scraper. Contrast this with a current Utube video tutorial which demonstrates how to apply beeswax to linen thread!

“Have the pupil cut from a 1-2” board a piece 2″ x 11″. With the use of axe, plane, tenon-saw and knife prepare an oblong 9-32″ x 1 9-16″ x 9 1-8″. Place drawing upon one of the sides and with the use of tenon and turning-saws cut to within 1-16″ of the line. Cut with the knife and file up to lines. Round and sharpen edges according to drawing. Finish with file, scraper and sand-paper.” (Schwartz, Project 10)

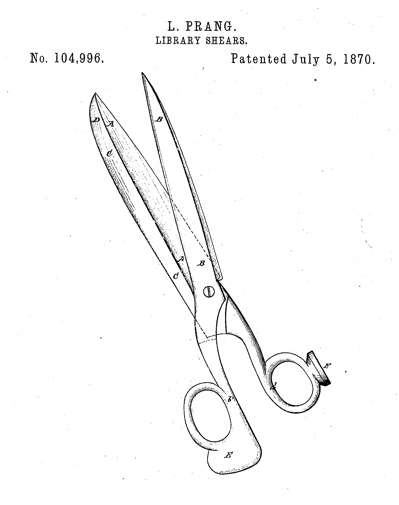

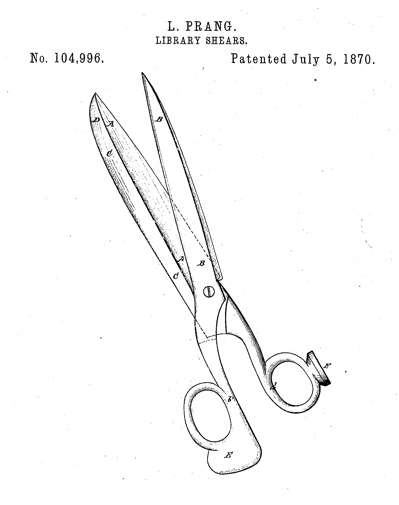

The coolest paper knife I have found is this patented combo paper knife (C), shears, eraser (D), paper folder (E) and seal (F). This is supposed to combine all the tools a librarian or clerk normally uses into one, convenient package. Today, we would likely call the “eraser” a scraper. I can’t see how the paper folder could be used without grasping the sharp edge of “C”, though the patent says all the functions can be used without interfering with the each other.

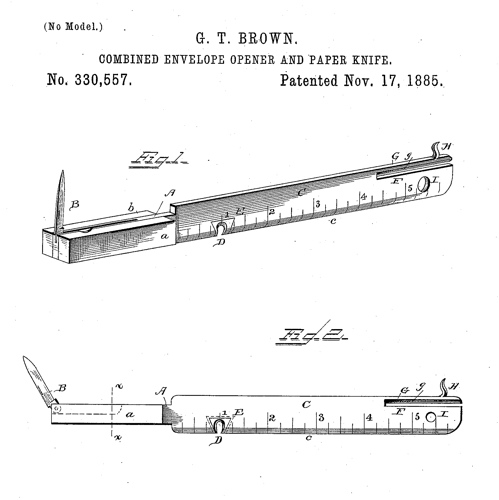

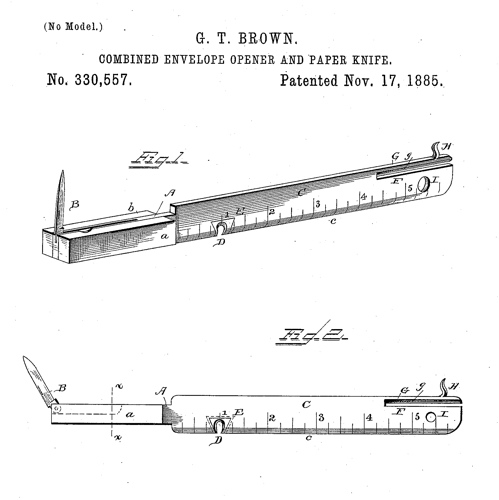

A close second is the combined paper knife (c), ink-eraser (a), rubber or pencil eraser (b), twine cutter (D), ruler (C), envelope opener (G), pen-knife (B), newspaper-wrapper opener (H) and hang hole (I). The patent notes the handle (C) can be made of ivory, bone, metal, wood or any other suitable material.

Any images of other paper knives, or information on how they were used, or images of them in use would be greatly appreciated.