Conservation Hand Tools: Making, Modifying, and Maintaining

Workshop Description

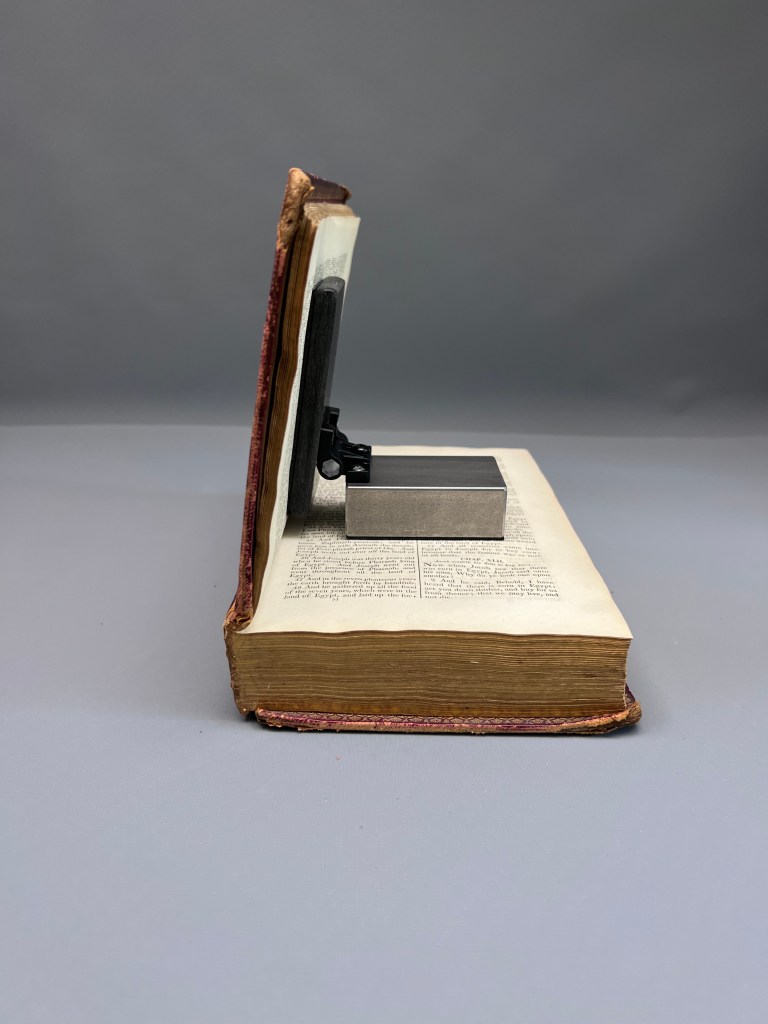

Most interventive conservation treatments are mediated through hand tools. Many of these tools had their origins in particular craft traditions; but conservators often modify them for particular uses. Tools become embodied in use, extensions of a conservator’s hand, sense of touch, and intention. Personal hand tools often become prized arrows in a conservator’s quiver.

This five day workshop emphasizes simple and safe methods of working hardened tool steel, stainless steel, Delrin, wood, and bamboo. Progressively more difficult techniques will be introduced during the week using primarily hand tools. This workshop will be tool-centric; for example, hand sawing — with the appropriate blade and technique — will be used for all the materials introduced. Choosing materials appropriate to the desired task will be emphasized. Possibilities include tools for cutting, folding, prying, delaminating, lifting, scraping, and burnishing.

Participants will complete a number of tools of their own design during this workshop. Examples of common existing tools — such as delaminating or lifting tools — will be provided as prompts. One goal is to free participants from the plethora of misinformation and mystique that surrounds knife sharpening, and learn fundamental freehand techniques applicable to any edge tool. Another is to gain competence in mechanical problem solving and practical hand tool use. Participants are encouraged to bring their own tools for discussion, possible modification, and repair.

Making tools is engaging, fun, and useful. It is also highly addictive. Consider yourself warned.

Workshop topics

• Basic tool use for stock reduction: sawing, filing, abrading, scraping, drilling, tapping

• Understanding what makes something sharp, efficient hand sharpening

• Tool design and mechanical thinking in general

• Making a high carbon, M2 tool steel knife by stock reduction

• Differences and similarities in shaping Delrin, Wood, Bamboo, and steel

• Tool handles, sheaths, and handle ergonomics

• Connoisseurship of vintage tools and tool maintenance

• Safe use of power tools

Please join us for an intensive toolmaking week at Emory University October 7-11, 2024!