“Keep Dark. Can’t Tell” With these four words, 19th century NYC bookbinder John Bradford begins an extraordinary book of bookbinding related poetry and imaginative parody. Written records from craftsmen during this time are very uncommon. Writings from bookbinders are very, very uncommon.

Bradford’s well-known poem, The Binder’s Curse, contains an introduction which places it in the context of a trade dispute, which is not so well known. The full title of the book gives a hint at Bradford’s wacky worldview: The Poetical Vagaries of the Knight of the Folding-Stick of Paste-Castle and The History of the Garrett, &c. &c., Translated from the Hieroglyphics of the Society, by a Member of the Order of the Blue String, Printed for the Author, [New York], 1815. The title is not just poetic exaggeration; part of the text consists of — supposedly — translated and untranslated hieroglyphics.

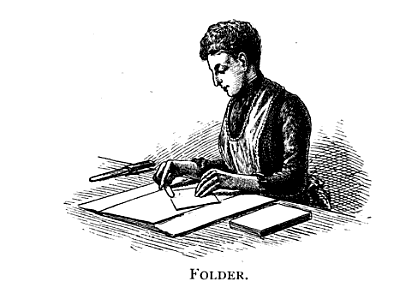

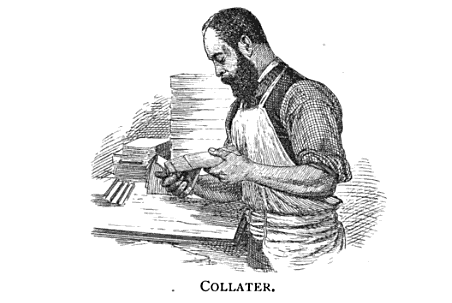

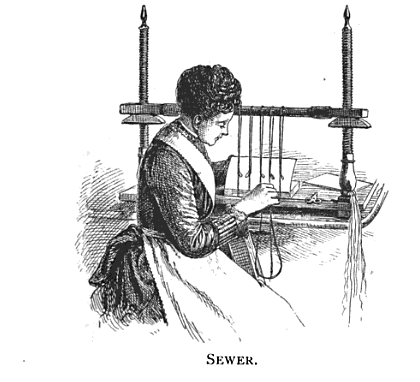

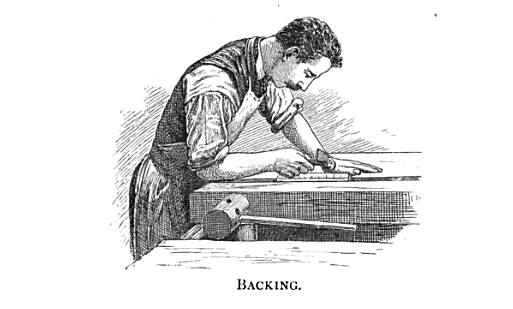

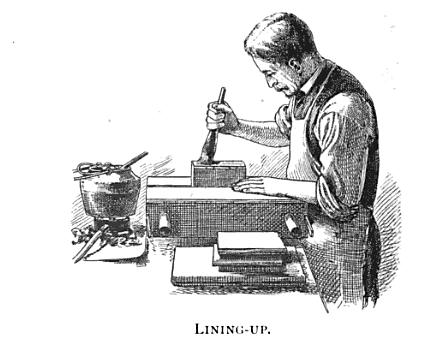

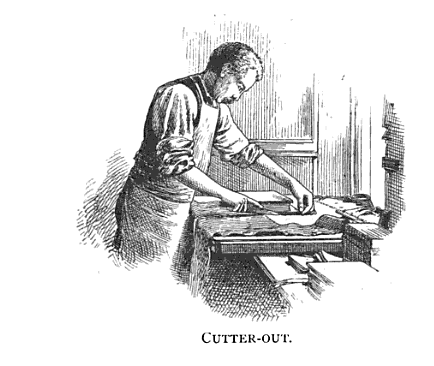

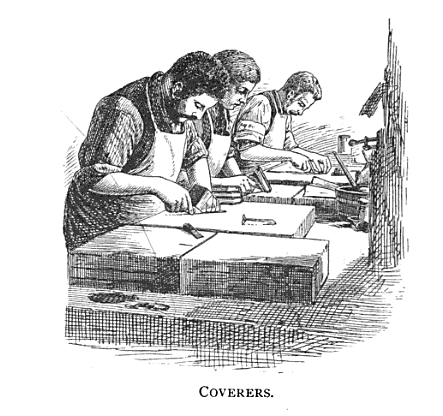

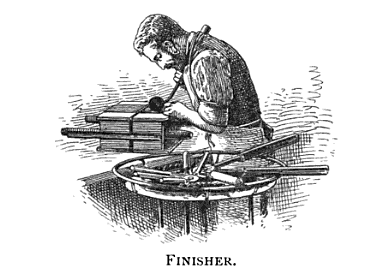

“This world’s a huge bindery…” Bradford proclaims, decades before Mallarmé’s more famous dictum, that everything in the world exists to end up as a book.1 Bradford constantly reinforces this world-as-bindery cosmology: Did this guy ever think about anything but bookbinding? Yet these poems provides primary documentation of bookbinding techniques and tools: the first mention of a squaring shears, details of which tools the binder owns (Bradford was a journeyman his entire career) and which the master provided, the use of templates, and more. There is a lot of serious bookbinding history buried in his poems.

There are also less serious aspects, like some really cringey love poetry. “Her forehead is like a paste bowl / And smooth as a fine paring stone.” Anyone want to guess what body part is “white as wheat paste”?

Bradford gives us a sense of the working life of an early nineteenth century binder, including day-to-day annoyances, and trade politics, all written with his relentlessly quirky sense of humor. The poem “Receipt for binding a book” consists of the earliest comprehensive listing of the steps in American binding, which is analyzed in depth by comparing it with extant bindings and relevant bookbinding manuals of the day. Bradford’s poems provide a insight into an imaginative bookbinder working on the cusp mechanization, especially dealing with the importance of tool ownership and use.

Thanks to editor Julia Miller and publisher Cathy Baker of the Legacy Press. And congrats to all the other authors below! I can’t wait to read the other essays. Available soon from Oak Knoll Press.

KEEP DARK

- Malarmé, “Les Livre, Instrument Spirituel,” Quant au livre, 1895. ↩︎