Three years ago I visited the Capitaline Montemartini Museum in Rome, Italy. In August 2012, I had a chance to revisit it; once again, it blew my mind. I wrote a post about my first visit, but wanted to add some new impressions and images.

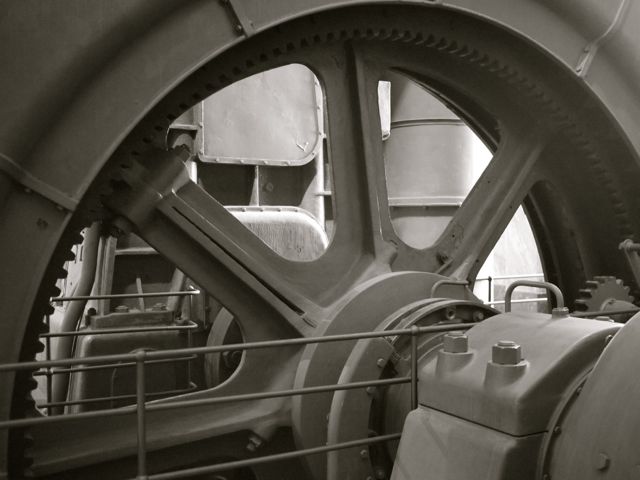

Briefly, the Montemartini Museum is an art nouveau electrical power plant that retains its original architectural details, and now functions as a museum which displays Roman sculptures alongside the defunct machinery. Montemartini originally used both diesel and steam engines to create electricity. The largest one is a 7,500 Hp diesel engine which was installed in 1933, and is about 20 feet high and 40 feet long. The sculptures belong to the Capitoline Museums (Museo del Palazzo die Conservatori, Museo Nuovo and Brassio Nuovo) and were installed in 1997 as a temporary exhibition. The exhibition proved popular and was made permanent. It is a uniquely powerful, stimulating and intriguing place.

This museum does not just contain, display, and interpret art: it is art.

Montemartini is a bit of a guilty pleasure for me. Frankly, I often find it more rewarding to spend time looking at industrial artifacts, craft objects, machines and tools rather than art. Quite likely this is why I am attracted to books: a few books are art, some contain art, but most are products of technology. Montemartini challenges the traditional divide between technology and art: here, we are not quite sure which is which. From some viewpoints, the statues visually merge with the engines. The functional and aesthetic aspects are in constant flux; at times becoming inverted, at times irrelevant, but always interesting.

Despite the omnipresent engines, machines and turbines, it is easy to forget you are in a factory. It is a beautiful space with elaborately tiled floors, symmetrically aligned turbines, lovely light fixtures, and elegant cast iron stairs and handrails. Massive windows on two sides of the engine room make it a clean and bright place, in stark contrast to the matt black engines. The statues are arranged around the engines as if they are guarding them.

The machines and statues feel like they belong together; equally portentous and aesthetically rewarding. This is perhaps the oddest thing about the museum. These objects, which come from radically different cultures and intended functions, exist naturally and peacefully together. Art is conflated with the Machine—perhaps the most unholy union imaginable—but it works.

Montemartini is a museum of fragments, not complete arguments or a comprehensive history. The paring of these machines and statues creates many entry points for inquiry: Art vs. Machine, blackness vs. whiteness, functionality vs. representation, art vs. craft, applied vs. abstract, technical vs. aesthetic, and possibly most importantly, body vs. machine. Machinery becomes aesthetically endowed; the statues appear as workers from the past tending the machines, not art. The statues are almost all damaged: torsos without arms, half a head, most with a nose or ear missing. The machines themselves are dysfunctional and only their shells remain. They are now disconnected from the grid, as mute and powerless as the damaged statues. Is this museum of pieces reflective of an unpleasant essence of all museums? Artifacts on display stripped of their original functions and significance? Is Montemartini a critique of musemification in general?

Although the machines and sculptures are visually balanced, primordially, the smell of the machines predominate. They smell of dark earthy oil, grease, and metal filings. They seem to have stopped only moments ago. The sculptures emit no smell. These white, etherial ghosts have been clawed from eternal repose only to be redeposited into an eternal waiting to begin work once again.

Superficially, there are corollaries with the Barnes Foundation. But in the Barnes the Art seems to dominate, while the smaller objects around the art function as a decorative frame, albeit a stimulating one. I need to think more about this.

For some reason, Montemartini also reminded of the temple complex of Angkor Wat, Cambodia. There is an analogous tension in Angkor, not of Machine and Art, but of architecture and nature. In Angkor, the stones of the temples are carved and decorated, slowly overtaken by the ficus tree roots and limbs, which both destroy and support the massive constructions. It is the peaceful coexistence of two extremes that form their commonalities between these unique sites.

“Expressions of power” was the essence of my first response to this place three years ago. This time, however, I was more struck by the fragility of the machines and sculptures. They both seemed delicate, as if a loud voice could disturb their equipoise. A handful of other visitors to the museum spoke in subdued voices, and walked quietly. No one wanted to disturb this postmodern tableau. Or was this mashup so disturbing in its conflation of traditional categories that we did not want our presence noticed—perhaps, so that we would not be obligated to recall it?

The Centrale Montemartini Museum is a complex, contradictory place. It raises many questions. If the ability for a work of art to generate varying interpretations with repeated encounters over time is a mark of quality, Montemartini is not only art, it is great art.

We did not see it while in Rome, but bought the book, which is easy to get lost in. Great post!

so glad you got to see this museum!

extraordinary vision and collaboration making it all happen.

M

Fantastic!

I visited this museum as a student in Rome some 15 years ago.

Perhaps I knew what it was at the time, but I think not. I have had no memory of what the story or place was, though I have vivid memories of the “place” and “environment”.

I immediately recognized the museum with your photos and was fascinated by the story behind the mental image/experience still so vivid in my memory many years later.

Thanks.