Written by Ashleigh Ferguson Schieszer, Special Collections Conservator and Co-Lab Manager of the Preservation Lab of the University of Cincinnati. Reblogged with permission. Originally published 27 November 2023.

Last year around this time, the lab was fortunate to bring in book conservator and toolmaker, Jeff Peachey for a week-long intensive workshop to learn leather rebacking. While I always expect to walk away with new anticipated skills as advertised by the workshop, I’m ALSO always pleasantly surprised by the tangential tips and tricks shared along the way. In the case of Peachey’s workshop, there were many!

One of my favorites was his use of a fish gelatin. While adhering spine linings to our text blocks, Peachey pulled out a small baggie of fish gelatin he brought with him to the workshop. He poured the dry flaky powder into a small jar, added room temperature cold water, and mixed it until a liquid-y consistency. He then added strained wheat starch paste to the gelatin and mixed with water until he was happy with the consistency. He estimated it was a 40:60 ratio of gelatin to paste.

If you’ve ever used gelatin before, you might be wondering – how is it possible to mix the gelatin without heating? That’s the beauty of this product – it has a high molecular weight with low bloom strength and is produced from cold water fish which gives it this ability. It might not be the strongest of the films with a 0-bloom strength, but for a book conservator doing paper repairs that need to be reversible yet strong, this combo still had an amazing tack when dry!

Peachey explained he first heard about the gelatin on a lab tour at the Weissman Center. He recalled Alan Puglia might have been the one who originally investigated the adhesive for pigment consolidation of hundreds of manuscripts for a show. The mention of a high molecular weight Norland fish gelatin was shared during a talk given at the American Institute for Conservation’s 44th annual meeting. The talk was titled, The Challenge of Scale: Treatment of 160 Illuminated Manuscripts for Exhibition,” by Debora D. Mayer and Alan Puglia.

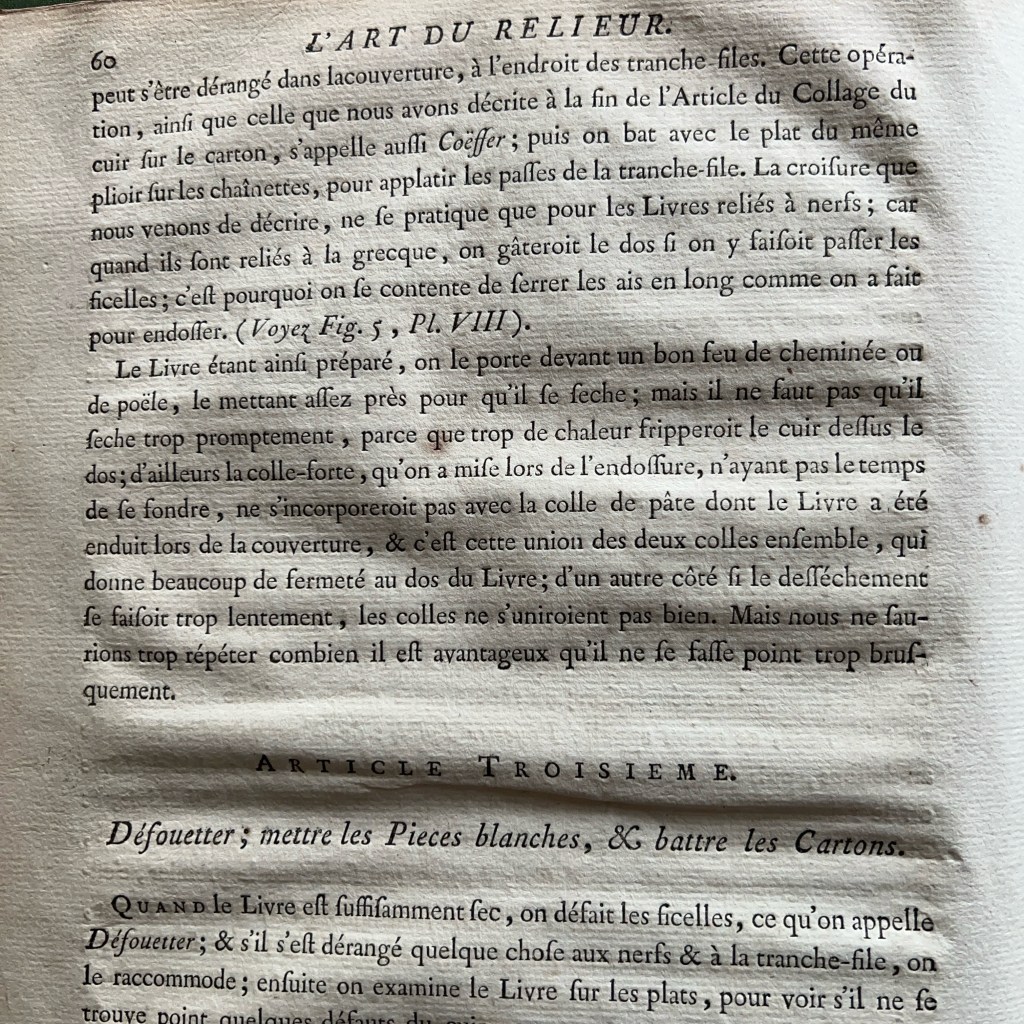

Peachey also doesn’t take credit for mixing the gelatin with wheat starch paste. He notes that even in Dudin’s 18th century manual, it discusses the “union” of paste and glue in the last paragraph below.

“It is the union of the two pastes [hide glue and flower paste] which gives a great deal of strength to the back” Dudin, 1772

By the end of the week-long workshop, I had fallen in love with the properties of how well it adhered. By itself, the fish gelatin had a long working time and didn’t stick until it was nearly dry – but when mixed with wheat starch paste, it combined the best of both worlds. There was both the initial tack from the paste and a strong adhesion from the gelatin after dry. I wasted no time in ordering my own sample supply.

Over the past year, I’ve slowly incorporated the fish gelatin in treatments and testing more applications.

I first successfully used it to hinge-in heavy encapsulated sleeves into an album containing lung cross sections. After ultrasonically welding a paper hinge into an encapsulated sleeve, I applied the mix of wheat starch paste and fish gelatin to adhere the hinge to the scrapbook stubbing and had wonderful success. I was able to adhere with confidence that the encapsulation would stay in place and was able to avoid disbinding and resewing. At one point during treatment, I found I needed to reposition a hinge. I am happy to report the mixture was as easily reversible as wheat starch paste alone!

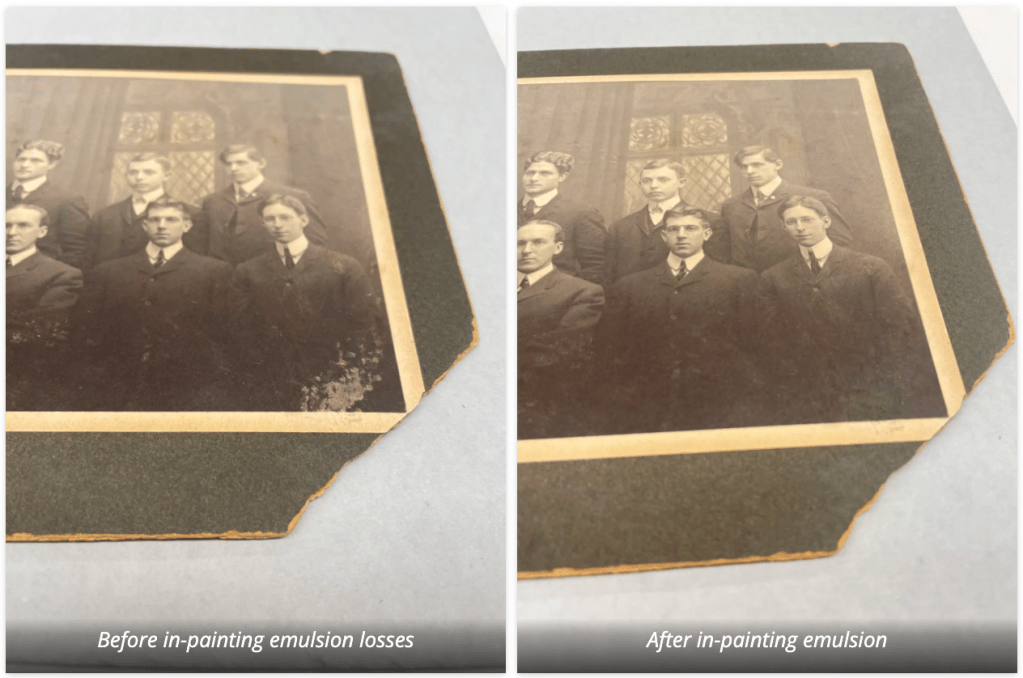

Most recently, I played around with using it for photographic emulsion consolidation. I used it first as a barrier layer before inpainting, and then to add sheen to in-painted photograph regions that were originally matte in comparison to the surrounding gelatin coating. It seemed extremely easy to apply and clean up was less messy than other photographic gelatins I’ve used in the past. The sheen was just the right amount of gloss I needed without being overly shiny. And, best of all, no heat required.

We’ve also used the gelatin to stabilize breaks in a wooden box originally used to house a Richter’s architecture game from the early 20th century. Jeff Peachey’ main use is to line spines. He’s found it not only has better adhesion than straight paste, but makes the spine feel slightly more solid and resistant to torsional forces

In the future, I imagine this gelatin would have excellent potential in media consolidation. In all these uses, I couldn’t be more thrilled to not have to pull out my baby bottle warmer to set a beaker of gelatin on. As a result, there was no fuss in worrying about how long the gelatin was heated and if it was losing its properties due to heat!

In terms of shelf life, the dried granules can be kept indefinitely like unmixed wheat starch paste. Once mixed, Jeff suggests that he’s found the adhesive properties hold up for about a week in the fridge; however, it does begin to smell fishy after just a day. So unlike wheat starch paste, if you’re adverse to the fishy odor, you’ll only want to make up as much as you’re planning to use for one day.

Interested in getting your hands on some?

I found the product used at Weisman is no longer supplied by Norland, but I was able to track down what appears to be the same product through AJINOMOTO NORTH AMERICA, INC. If you’re interested in trying it, message Henry Havey, the Business Development Manager of Collagen & Gelatin at haveyh@ajiusa.com to request a sample of High Molecular Weight (HMW) dried fish gelatin.

They provided me with a 500- gram sample at no cost and confirmed it was a Type A fish gelatin with a zero bloom strength. Henry Harvey can also provide a pricing quote should you be interested in ordering a full supply which comes in 25 kg packs. They also provided the following product data info sheets.

While I still covet my isinglass cast films I created from boiling dried fish bladders, as well as our mammalian photographic grade type B gelatin, this HMW fish gelatin is a welcome addition I’ve added to my tool kit.

Ashleigh Ferguson Schieszer [CHPL[] – Special Collections Conservator, Co-Lab Manager

Bibliography

Dudin, M. The Art of the Bookbinder and Gilder. Trans. by Richard Macintyre Atkinson. Leeds: The Elmete Press, 1977, p. 51. (Originally 1772)

Nanke C. Schellmann, Animal glues: a review of their key properties relevant to conservation, Reviews in Conservation, No. 8, 2007, pages 55-66

Foskett; An investigation into the properties of isinglass, SSCR Journal ; The Quarterly News Magazine of the Scottish Society for Conservation and Restoration, Volume 5, Issue 4, November 1994, pages 11-14

World Sturgeon Conservation Society, A Quick Look at an Ancient Fish, 4th International symposium on sturgeon, Oshkosh, Wisconsin, July 8-13, 2001 https://www.wscs.info/publications/proceedings-of-the-4th-international-symposium-on-sturgeons-iss4/

Soppa, Karolina; Zumbuhl, Stefan; and Hugli, Tamara, Mammalian and Fish Gelatines at Fluctuating Relative Humidity, AIC 51st Annual Meeting, 2023