The urge to preserve, is, perhaps, as old as the urge to eliminate.

.

Book Conservation

The urge to preserve, is, perhaps, as old as the urge to eliminate.

.

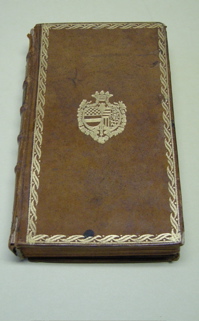

For reasons unknown to me, there are a number of these late 18th C. French bindings that have been converted into smuggler’s bibles. The stamping on the front cover was done at a later date, and the inside of the textblock seems to have been edge glued, and the back flyleaf used to line the edges. The bottom is the back board pastedown. I always wonder what happened to the bulk of the text– thrown away or burned, most likely.

So if I am “reading” this book correctly, with little or no text, it is the materials and the structure of the binding that give it meaning. In a way, this book is a eloquent example of how a conservator approaches a book. Firstly, through the lens of the history of technology, it is the physical substrates that support and protect the text that are documented, analyzed and conserved. Secondly, we have not time, interest or are unable to read the language of most of the books we work on. Do we even need the text?

But this book also demonstrates how the brutal alteration of an artifact can distort our understanding of history. I’m very interested in late 18th C. French bookbinding, and even though there are many extant examples, each one that is lost distorts our understanding of the total production and subtle workshop variations. It is that it is very difficult to determine when this book was altered, so it gives the unscrupulous an easy excuse of saying they bought the book in this condition. The market currently values destroyed or altered books such as this more than an intact volume.

There is even a company called “Secret Storage Books” that currently makes new versions. If I were being more stringent with my own ethics, I guess I shouldn’t have purchased this book, since it encourages more of them to be made.

Octave Uzanne, writing in 1904, in The French Bookbinders of the Eighteenth Century writes: “‘Sham books’, simple wooden boxes, and sometimes mere mouldings, covered with gauffered and gold-tool leathers, with which they filled the empty shelves of a pretentious library, or with which they garnished the doors.” The books below, however are real books that have been made to resemble the sham books he talks about.

Jane Eagan kindly sent this image of a similar book she owns.

On the 24th of March, 2009 I was watching Looney Tunes historic Chuck Jones animation, and from 1939 an 8 minute short titled “Sniffles and the Bookworm” featured a smuggler’s bible. Watch the book on the bottom right. I barely had time to grab my camera, so I missed a better shot earlier in the movie.

At first, I thought the above knife was a German style paring knife, but now I’m not so sure. German knives are almost always somewhat flexiable, and this one is very rigid. Notice the small recess on the handle, near the blade, perhaps worn by fingers gripping the handle over the decades. Even a light surface cleaning could destroy not only important use evidence, but the overall beauty of the knife. As I have said before, the over-cleaning and “restoration” of hand tools is perhaps the most significant ongoing loss of cultural property that commonly occurs. The blade is full tang and has a gradual taper in thickness towards the cutting edge. Judging from the scratch patterns in the top picture, the owner must have had a stressful encounter with his grinding wheel! But I find these marks interesting evidence of the history of the tool, as well as a visually refreshing antidote to the ubiquitous monotony of the highly regulated machine grind marks found on new tools. The handle is an unidentified light colored wood that has been stained and is still firmly attached to the tang. The edges of the handle is still quite sharp, and the various ways I have tried to hold it all are somewhat uncomfortable.

Matt Murphy found some information about Fred J. Birck: “From 1903-04 he worked at 93 Essex St. In 1905-06, Fred. J. Birck is listed as being a part of Birck & Zamminer Cutlery, which is located at 154 Essex St. In 1908-1912, Birck is listed at two seperate addresses, 132 Essex St. and 17 Cooper Sq. East. In 1912-1913, the primary address is changed to 17 Cooper Sq. E. In 1913-1914, the partnership must have been dissolved, because only Birck is listed, and the only address is 17 Cooper Sq. E. until 1925. Also, Mr. Birck made his home in Jersey City, New Jersey, as his address is often listed as 144 Hutton St. (Which still stands to this day.)”

So the knife is possibly from 1913-25. Aside from the beautiful, insanely deep makers mark, I was attracted to the fact that another knife-maker worked in the East Village of NYC, only about 5 blocks from where my studio is now. There is even an old bar, McSorley’s, established in 1854, still operating right around the corner from Birck’s 17 Cooper Sq. address. Perhaps Birck had a drink there. I’ll raise a glass to him next time I’m there.

Don Rash posted a similar looking knife on his blog, unfortunately no makers mark. I looked through Salaman’s Dictionary of Leather-working Tools c. 1700-1950 and couldn’t find any similar knives, and Salaman covers some pretty obscure leather-working trades ( ie. gut string maker, hydraulic pump-leather maker) but tends contain more English rather than American references.

Below is the German knife from Zaehnsdorf’s The Art of Bookbinding, 6th Ed. 1903. It almost looks like the knife is shaded more heavily on the top edge, to make clear the blade tapers toward the other edge?