Book conservation, possibly more than any other conservation discipline, consists of a skill set that is closely linked to its craft roots. Conservators must not only be able to intellectually understand the mechanics, chemistry and history of book structure, but also need the hand skills to actually do bookbinding: performing, for example, a full treatment where a text needs to be rebound in a style sensitive and sympathetic to its structural requirements and time period. So what prompted Christopher Clarkson to write, “European hand bookbinding practice does not form the best foundation on which to build or even graft the principles of book conservation.” (Clarkson, 1978)

Although written 30 years ago, these words are still extremely provocative. In a very narrow interpretation, the phrase “ European hand bookbinding practice” could mean typical trade bookbinding practice, and the statement is entirely uncontroversial— not every book should be rebound and of course a 10th century manuscript should not be stuffed into a typical late 19th century trade binding! (1) But what if Clarkson is pointing towards a broader reading, establishing a dichotomy between bookbinding and book conservation, potentially even between a craft and a profession? Given the close relationship of the two, how could they be separated?

A few clues can be found elsewhere in the same volume of The Paper Conservator. This issue begins with a policy statement, noting four basic purposes of publication:

“1. To conserve the traditional crafts of conservation… . 2. To stimulate the craftsmen to develop a methodology with which to record their techniques and experience… . 3. …extending knowledge about craft techniques in closely related fields… . 4. To assemble a reference source of craft techniques for trainee conservators.” (My italics) (McAusland, 1978)

These multiple references to craft are perhaps even more shocking that Clarkson’s original quote, and somewhat explain his need to propose a break with the past, at least in a philosophical context. It appears that in 1978 that book conservation was considered a craft, or at least craft was a large part of it. But professionalism was on the rise at the same time; Paul Banks was elected President of AIC in 1978 (a first for a book conservator) and his The Preservation of Library Materials was published the same year. Did a rise in professionalism necessitate a break with craft tradition in order to escape habits, both in thought and praxis, built up over centuries?

I am certain that if I mentioned “the craft of conservation” in 2008, I would be greeted by suspicion, jeers and critical blog posts from my peers. Today, conservators have, to a large degree, distanced themselves from that dirty little word—craft– at least in their own minds.(2) This distancing seems to be the core message in Clarkson’s statement, as a necessary first step. In order to rationally and objectively approach a conservation treatment, it was necessary to step outside of the preconceptions of a craft tradition, and attempt to examine the book and the goals of the treatment from the outside. Sometimes a conservation treatment might closely resemble how a bookbinder might repair a volume; sometimes it might be radically different.

How can the craft of the bookbinding be preserved in a professional context that has struggled to escape its craft based roots? Are there dangers, however, of completely refuting the craft of bookbinding while formulating a new theory of conservation? Almost 1,700 years of mostly unwritten craft skills have been passed on during the history of bookbinding. Many structures and techniques have been abbreviated, forgotten and lost. Some have been rediscovered later, existing as primary evidence in book structure, or extrapolated through praxis. A conservator could start a treatment, with no knowledge of bookbinding technique, but if the treatment was at all complex, it seems the conservator, even if ignorant of craft technique, would end up reinventing it. Maybe this is how the craft will survive.

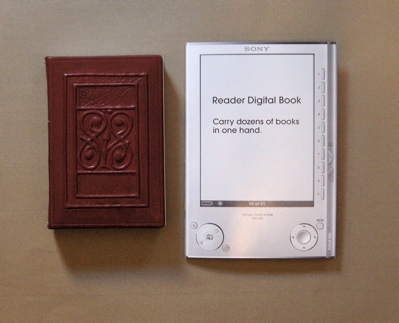

As books cease to be viewed as primarily a vehicle for transmitting textual information, and move closer to object-type status, I predict the physical information their materials and construction contain, and their visual appeal will become increasingly valued. (3) Paradoxically, we may have to wait until books no longer fulfill their original function (to be read) before we fully value the craft skills that created them, and then will have to rediscover those skills.

In another 30 years, perhaps, the field of book conservation will be mature enough to reexamine its relationship to craft. Hopefully some of the craft skills will still be present or rediscovered, and might be reincorporated into some future conception of conservation.

NOTES:

1. Ironically, this style of binding, with all of its structural faults, remains the ideal of fine hand bookbinding in most of the public’s imagination.

2. Most of the public, unfortunately, uses the terms bookbinder, master restorer and conservator interchangeably. A paramount task for conservation is to educate the public on these differences.

3. In the past year or two, I have noticed more private collectors wanting a cradle for their book so that it can be safely displayed in their home.

REFERENCES

Clarkson, Christopher. “The Conservation of Early Books in Codex From: A Personal Approach: Part 1.” The Paper Conservator Vol. 3 (1978): 49.

McAusland, Jane. “Manual Techniques of Paper Repair” The Paper Conservator Vol. 3 (1978): 3