Three years ago, I wrote a post about board shears and their relationship to boarded and early case binding. But before the board shear (aka. board chopper, table shears), which likely entered bookbinderies in the 1830’s, millboard shears were used for trimming book boards square. They are essentially large tin shears, bench shears, or tin snips as they are commonly referred to. I had never seen a pair of these, except in early manuals and in a great photo from Middleton’s Recollections on page 37. The caption for the photo, taken in 1999, notes that this was the first time he had used them since 1960.

But a couple of weeks age, I found something very similar in an antique store…

Fig. 1. Large tin snips with a 12 inch ruler on the bottom.

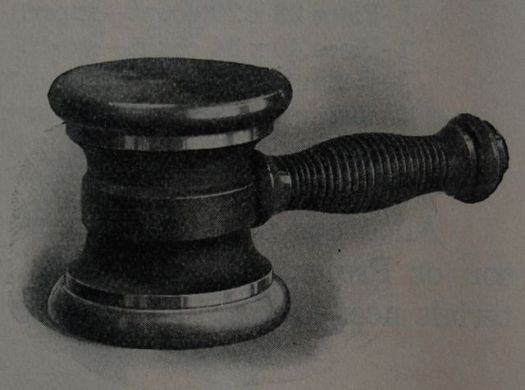

Although I think these are actually large tin snips, but I doubt that there is much difference if they were made for metal or binders board. The Peck, Stow & Wilcox Co. lists an almost identical bench shears, availiable in a variety of sizes. Likely, earlier ones were a bit larger than my example, but this size works quite well. They will be interesting to use in the workshop I teach on early 19th century bookbinding –bringing us one more step closer to using tools appropriate to the time period of the binding. This shear has a 6″ cut, and is stamped “Roys & Wilcox Co. / East Berlin Ct. / Cast Steel / 5 ” The slight bend to the end on the top handle on the upper arm, is very important, because it keeps the heavy arm from pinching your hand as you operate the shears. The other handle was bent, I believe, to insert into an anvil for the smith to secure it while cutting. The shear is quite stable when clamped in a lying press.

Fig. 2. Mill board shears in action.

The Whole Art of Bookbinding, 1811, simply mentions cutting out of boards with “the large shears” (p. 8) Martin, in 1823, states that “The pasteboards being roughly cut with shears to something like the size (p. 14). Cowie, in 1828, interestingly mentions a “press-shears” for squaring the boards after lacing on, which must refer to these types of what later became know as millboard shears (p. 19). Middleton notes that millboards were availiable to binders as early as 1711, and the last hand-made millboards maker ceased production in 1939. Did the name, millboard shears stick, perhaps because paste boards were soft enough to be cut with a smaller shears or knife? French bookbinders, from around this time, used a large pointe to cut their boards.

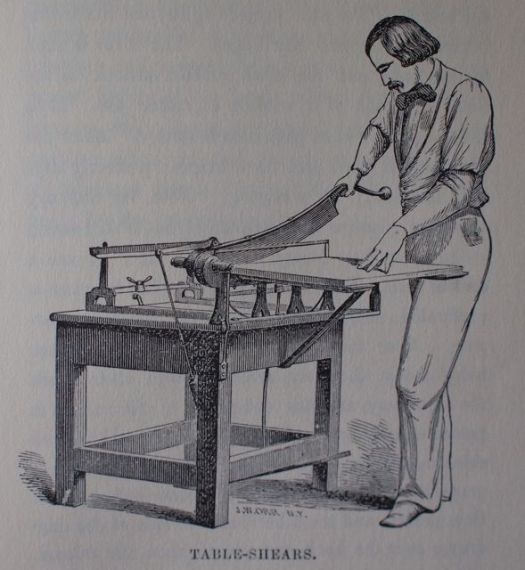

Fig. 3. Nicholson’s table-shears. Observe the lack of gauges for cutting-there is only an outer gauge, the foot clamp, and the graceful positioning of the worker’s left hand and feet.

Fig. 3. Nicholson’s table-shears. Observe the lack of gauges for cutting-there is only an outer gauge, the foot clamp, and the graceful positioning of the worker’s left hand and feet.

Nicholson, in 1865, makes no mention of the millboard shears, but does refer to board shears as “table or patent shears” (p. 65), suggesting this was still a somewhat new machine, at least in the US? One can almost imagine the evolution from a millboard shear, somewhat difficult to use because of its short cutting length, being reconfigured with larger blades, one fixed, like clamping the bottom blade in a press, and a handle, added for leverage on the other. The table also prevents flexing of the board, which improves accuracy in cutting. Note that the table shears In the 1920’s or 30’s, Hickock, in catalog #88, subtitled their board shear as a “Gauge Table Shears”, on page 10.

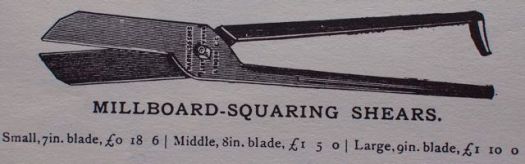

Fig. 4. Image from 1892 Harrild and Sons catalog of millboard shears.

The Harrild and Sons catalog has a picture of their ‘millboard squaring shears”, stamped with their logo– note the the market was large enough for them to carry three different sizes, a 7″, 8″ and 9″.

Fig. 5. Crane’s illustration of how to lay out mill board for cutting with the millboard shears. This is very similar to how French boards were cut 100 years earlier.

Crane, in 1885, somewhat oddly, provides the above illustration for the marking of millboard for cutting with a millboard shears but does not include an image of the shears. First the boards are divided with a large compass, marked off with a bodkin, then the cutting lines drawn using a straightedge. He does include instructions on how to use the millboard shears. “The Boards are generally cut up with the millboard shears. These are screwed up in the end of the laying-press nearest to the operator, and, the millboard being placed between the jaws, the dege of the upper jaw coenciding with the mark upon the board, the upper handle is worked by the right hand, and the board is readily and quickly cut. The millboard is held in the left hand during the operation. In most regular establishments of any pretensions, the shears are now almost superseded by the board-cutting machine… (p. 67)”

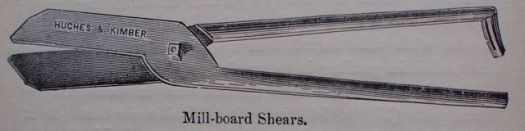

Fig.6. Image of Mill board shears from Zanesdorf.

Zaehnsdorf, 1903, also provides some instruction on how to use mill board shears. “To use the shears, screw up [!] one arm in the laying press, hold the board by the left hand, using the right to work the upper arm, the left hand meanwhile guiding the board. Some little tact is required to cut heavy boards. It will be found that it is necessary to press the lower arm away with the thigh, and bring the upper arm towards the operator whilst cutting. (pp. 52-53)” The photograph of Middleton, in Recollections, shows this exact method of holding the board. (p. 37)

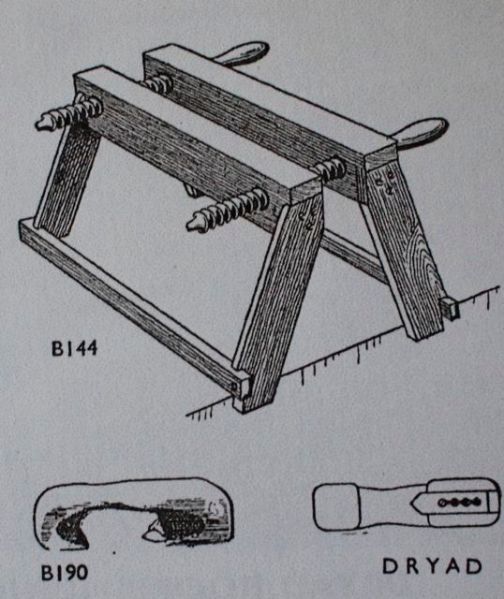

Fig. 7. Cockerell’s improved millboard shear attachment.

Cockerell notes that if “The straight arm of the shears is the one to fin in the press, for if the bent arm be undermost, the knuckles are apt to be severely bruised against the end. Any blacksmith will bend the arm of the shears and make the necessary clips. This method saves considerable wear and tear to the ‘lying’ press. Where a great many boards are needed, they may be quickly cut in a board machine, but for ‘extra’ work they should be further trimmed in the plough, in the same way as those cut by the shears. (pp. 126-127)” I’d be curious if anyone has a lying press with some telltale indentations at the ends? I wonder if board shears of the time gave a slightly rough, crude cut, or was it just tradition to later plough the edges? Ellen Gates Starr, an American who spent 15 months studying bookbinding with Cockerell, seems to mention this method of attaching the shear in the 1915 Industrial-Arts Magazine. “The boards are roughly cut to approximate size (We do it with a huge pair of shears of which one handle is made fast. I have never seen a pair except for my own in this country) (p. 104).” Were millboard shears that uncommon in the US? It seems that by the 1920’s, millboard shears had gone out of fashion. Thomas Harrison remarks in 1926, that, “…millboard cutters are now used instead of the shears…” (p. 65) But he includes an image of the Cockerell type attachment, although given the similarities of the renderings, I’m tempted to speculate that Harrison was at the least highly influenced by Cockerell’s drawing, or it may be a copy with slightly altered perspective.

Fig. 8. Harrison’s version of Cockerell’s attachment.

Fig. 8. Harrison’s version of Cockerell’s attachment.

In my own experiments, these shears cut binders board quite well. They are obviously slower to use than a board shear and take more skill to operate. With a fairly large sheet, it is difficult to rejig it with the blade for each cut, so a little longer blade would be advantageous. The reason the shears are often positioned about 45 degrees to the press, is so that they are roughly in line with the eye of the user. The thickness of the blade requires that the board be parted during the cuts. It is difficult to realign a cut when in the middle of it, so it the cut strays from the line, it tends to be for the length of the blades, which may a clue to identify how 19 century boards have been cut and what size millboard shears were used to make the cut. I’ve tried it on both Davey and Eterno board, .080 and .098 thickness, and I imagine, although haven’t tried, that large tin snips might do a decent job of rough cutting of sheets to size, before trimming with a straight edge and knife– easier for those who don’t have a board shears.

Even today, one of the most common difficulties, for those who lack a Kuttrimmer or Board shear, is trimming binders board to size. Cutting through a wide section of binders board is very difficult with an Olfa type knife and a straight edge– the board tends to pinch and squeeze the blade. Cutting a narrow strip (1/2″ or so)off the edge of a board is much easier, since the board can be pealed of pulled away, making room for the thickness of the knife blade. This is also why I prefer thinner knife blades. Millboard shears could be useful for binders who mainly do fine binding, and don’t make boxes, or for those who have a smaller Kuttrimmer, incapable of cutting a full sheet of board. Perhaps there is still a use for this almost obsolete bookbinding tool?

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tom Conroy for information on early board shears,the Middleton, and Peck, Stowe & Wilcox references.

______________________________________________

[NA] The Whole Art of Bookbinding. Owestry: N. Minshall, 1811.

Cockerell, Douglas. Bookbinding and the Care of Books. New York: D.Appleton And Co., 1902.

Cowie, George. The Bookbinders Manuel. London: Cowie and Strange, [1828].

Crane, W.J. E. Bookbinding for Amateurs. London: L. L. Upcott Gill, 1885.

[G. Martin] The Bookbinder’s Complete Instructor. Peterhead: P. Buchan, 1823.

Harrison, Thomas. The Bookbinding Craft and Industry. Garland Publishing, Inc: New York & London, 1989. [1926]

Middleton, Bernard C. A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique. New York & London: Hafner Pub. Co., 1963.

Middleton, Bernard C. Recollections: A Life in Bookbinding. New Castle and London: Oak Knoll Press and The British Library, 2000.

Nicholson, James B. A Manual of the Art of Bookbinding. Philadelphia: Henry Carey Baird, 1865.

Zaehnsdorf, Joseph. The Art of Bookbinding. London: George Bell And Sons, 1903.