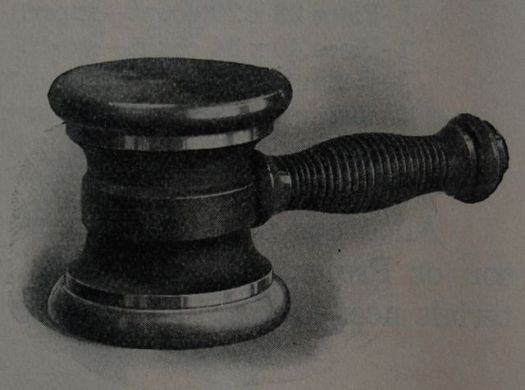

The hammer pictured below is a beating hammer, and it was made for beating paper and book board. At first glance, it seems to resemble a judge’s gavel, but the head is made of iron, not wood. It is slightly unnerving, yet distinctly pleasurable– an ‘anti-conservation’ experience– to repeatedly beat a textblock with a large hammer.

In late 18th century France, for example, the sheets and books were possibly beaten eight different times. In England, the beaters, a semi-skilled subset of bookbinders, were replaced by what is considered the first bookbinding machine, the rolling machine, in the 1820’s. Beating, or not beating, was also an important in distinguishing between ‘temporary’ structures, and more permanent ones.

Currently, beating hammers are notoriously difficult to find– I have been looking for over a decade. Since the practice of beating has gradually declined throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, many of these hammers must have made some kind of gradual evolution from working tool, to doorstop, to the bottom of the closet, then sold for scrap, or left to rust. Thanks to a hot tip from the anonymous bookbinder, I managed to purchase not one, but two last week.

The first one is a Hickock judging from the overall shape, even though it is not labeled. It is possibly a bit later than the one pictured in the illustration below, which came from Palmer’s A Course in Bookbinding (1927). The shape of the handle is very similar, but a bit simpler than the beaded handle pictured below, and the head is almost exactly the same, note the polished faces, edges of the faces, and the little rim.

The faces are about 3 inches in diameter and it weighs just under 5 lbs– fairly light by beating hammer standards. The Hoole catalogue No. 79 (1911) lists their selection from 5 to 14 lbs. Middleton, in A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique, reports seeing reference to 16-18 lb. hammers (p.7)

I’m a little unclear if this second hammer is actually a beating hammer, it could also be a gold beaters hammer, which often have a similar weight and face shape. This one weighs about 6 lbs. The handle it came with was very weak and deteriorated, so I carved a new handle in order to use the hammer, as well as polished the faces.

Traditional beating hammers had a bell shape, like the one pictured in Jost Amman’s bookbinder print (1568). This shape continued into the 19th century, like this Harrild & Sons beauty from 1892. I need a bell shaped beating hammer!

If you haven’t tried hand beating, it is instructive for appreciating why older books look, feel and function the way they do. Softer mouldmade and handmade papers can compress up to half the thickness, resulting in a solid, yet light book. The surface of the paper changes. Softer types of book board, such as paste or waterleaf, also compress. Some traditions even lightly beat the leather after covering. The unforgiving hardness of modern book papers and book boards is a modern affliction.

Beating hammers were used with a stone to beat on, although some sources report the iron was also used after 1800. Given the numerous dings and dents on the hammers I purchased have, I suspect they were used on iron. The surface of my Jacques board shear seems to have been used for beating, or perhaps rounding, at some point in its life, given its numerous dings and dents.

Contemporary reports that the stone, or iron, gives such a bounce to the hammer that most of the effort is stopping its rebound, not hammering downward. Middleton, summarizing some of J. C. Huttner’s Englische Miscellen (Band 6, 1802), states:

…the English beat their books harder than do the Germans (though not so keenly), due to the iron block and the standing position of the workman, but especially to the method of holding the hammer. German binders hold the handle so that the tips of the fingers meet underneath, whereas the English have their fingertips meeting on top, so that the back of the hand is underneath, and they strike the book slightly sideways. The hammer bounces back level with the ear from the iron block, and workmen can do it for days on end without complaint. On the Continent books are beaten twice, before folding, and before sewing, but in England, due to the efficiency of the standing presses [ wood frame with an iron screw-jp] it is necessary to beat before sewing only. (p. 253-4)

When making a historical model, using the proper tools adds to the authenticity of the fabrication experience. They certainly make it more fun. And I believe that they subtly, perhaps invisibly, influence perception of the completed model.

Beating hammers are rarely, if ever used for book conservation, so I suspect this one will primarly function as a weight, much like Nicasius Florer used his for in this painting from 1614.