Simplex Sigulllim Veritas. I bought this in Nepal in 2002. It functions beautifully, is made from the simplest of materials and costs virtually nothing to manufacture. A bolt, two nuts and a scrap piece of wood. But the man I purchased this from specialized in making or reselling these- he had hundreds, and it was a very common item in restaurants. To use it, it is turned upside down and the the bottle cap inserted at the end,then the head of the bolt lifts the bottom it off. I think I paid about 5 cents for it and it even comes with a hang hole.

1532 Press

This is a detail from the 12 brothers foundation, a link is listed in the post below. A few thoughts about the press pictured in the portrait of Hans Landaver, dated 1532. Foote identifies this as a small standing press. I think it is a German style press that is lying on it’s side– often these are used to clean spines or tie up when covering. It would make little sense to press a book like this once the bosses and corners were attached- more likely it is holding the book for purposes of illustration. Especially when viewed from this angle, it is uncannily similar to a sewing frame– in fact the edge of the bench almost mimics a top crossbar. This press is puzzling, and I can’t figure out how it would function. I assume the squarish nuts that form the ends of the screws would be used to tighten this press, but the smaller circles on them seem to indicate they don’t move along the thread. Possibly the wood is directly threaded? Maybe they function to keep the threads from pulling through, and both pieces of wood are drilled for clearance, and a nut would be attached from the other side? The thread angle is roughly 45 degrees, which would be unusable, but it is a fairly common artistic convention for the time.

Good Diehl

Edith Diehl’s “Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique”, thanks in part to an inexpensive and ubiquitous Dover reprint, is perhaps one of the most common introductory bookbinding manuals. Although frequently maligned for propagating innacuracies, especially the historical section, the practical section is informative and well done. I use her sequence of leather covering steps when teaching– it is a clear, calm list of what needs to be done. Panicking students, covering their first full leather binding, often find it reassuring. Her diagrams in general are concise and present the relevant information in an easy to follow manner.

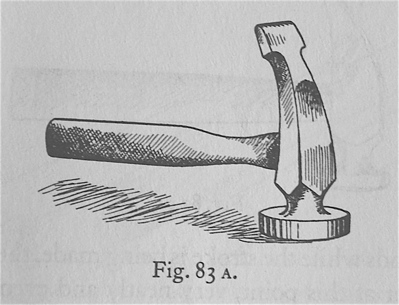

This hammer came from her studio, via Gerard Charrier, who purchased many of her tools. It is a large London pattern cramping hammer and according to Salaman, Barnsley’s 1890 catalog of cobblers tools lists six sizes of them, this one is a “No. 1”. It is similar to a French hammer and is used to paning the sole edge, heel breast and waists of shoes. He also notes that this style of hammer was already going out of fashion by 1839! The head is quite large, 55mm, so I don’t use it for binding- more often to tenderize pork when making tonkatsu, or in place of a proper beating hammer. Even though I don’t use it for binding, the feeling of using historic tools remains somewhat inexpressible. Touching the smooth worn areas at the end of handle, examining dirt near the head, or polished areas around the cheeks, gives me direct tactile and visual information about how Diehl held it. The makers mark is fragmentary, but it starts “CHAMMO…” with “CAST STEEL” stamped underneath. This hammer must have been the one she copied for the illustration below, unless she had more than one of them. The illustration is from page 143 of the Dover edition.

Diehl likes a large and heavy hammer, feeling they are less likely to damage signatures by leaving small indentations in the spine. She also makes the point that when using a heavy hammer, its weight does most of the work, so there is less danger of forcing it and damaging the signatures. She specifically recommends that the hammer should be weighted so that the face balances even if no one is holding the handle, as both the photo and figure clearly show. I find it a bit odd, given the attention to detail in most of her diagrams, that she didn’t depict the eye in this one. There are two photographs of students using a similar London pattern hammer in Palmer’s 1927 manual “A Course on Bookbinding for Vocational Occupation”, found on the frontispiece and on page 38. One is using the face to back a book, the other the peen.

I also have a book from Diehl’s library. Her gold stamped book plate is quite lovely. It only measures 35mm high and 27mm wide and I assume it is St. Jerome.

.