Fig. 1: Two grattoirs from Dudin, Plate 10.

In 18th century French bookbinding, according to both Diderot and Dudin, these grattoirs (usually translated as scrapers) were used to aid in backing and smooth the spine linings. There were also frottoirs (versions with dents– pointed teeth) [*check comments for some discussion of these terms*] to scratch up the spine to get better adhesion, since book structures of this time period often had transverse vellum spine linings. I made a wood copy of the tool above on the left, but the light weight and friction from the wood made it awkward and ineffective; the friction would tend to tear the spinefolds and dislodge spine linings. There is a contemporary version, available commercially, which is even more useless due to the extreme round on the ends. I’m a little uncertain about these terms– so far the only reference I’ve found in English is in Diehl, where she refers to a wood frottoir ( burnisher?), that looks a lot like the one still available.

Fig. 2: Two 19th century frottoir/grattoirs, courtesy Ernst Rietzschel.

This summer, I had a chance to test drive the combination frottoir/ grattoir tools pictured above. Ernst Rietzschel, from Holland, borrowed them from his bookbinding teacher in Belgium, so it is likely they come from the French binding tradition. Their weight, as well as the very slight curve, made it easy to concentrate pressure on just a signature of two for accurate manipulation of the spine. As an unexpected benefit, it was wildly cathartic to punch and scratch the spinefolds with the teeth, of course, only in the interests of historical research!

I used the smooth, slightly rounded ends of the original tool to back the book and to align the cords as well as to burnish the spine linings. Even with the damaged edges and paint, I was surprised how easy it was to gently control the backing process and tweak the cords into alignment. I had much more control compared to using a hammer, and it was quicker (and potentially less damaging) than loading the spine with so much moisture that I could manipulate it with my fingers or a folder.

Originally, I was planning to reproduce the original, but I didn’t want to make it out of iron because it is prone to rust. I wanted two smooth ends since I only scrape spines on specific historical models. I considered stainless steel, but didn’t have any on hand, and it is very gummy and difficult to work by stock reduction. Bronze was a good candidate, but brass is slightly harder.

So I made a modern interpretation out of free machining, type 360 brass with a lignum vitae handles. The quarter inch thick brass and heavy wood handles give it a weight similar to the original, although the aesthetics are quite different. My version is 1.5 inches wide, 8 inches long and weighs 9.4 oz. ( 4 cm wide, 20 long, and 266 grams) In practice it works just as well, in not better, than the original. It can be grasped with a fist for extra pressure, or delicately held like a pencil for detailed manipulation.

I wonder why a tool this useful would become virtually extinct?

Fig. 3: A contemporary grattoir I designed and made.

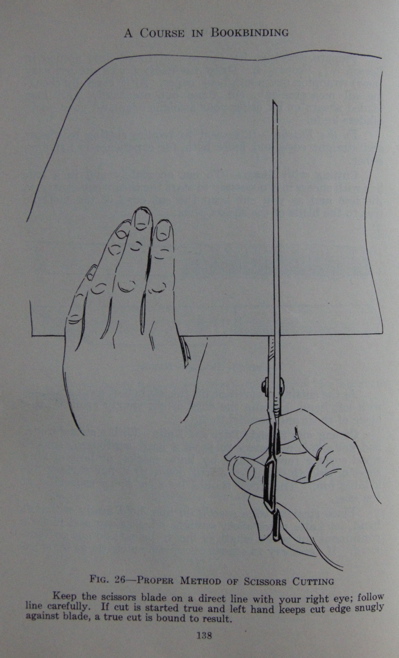

Palmer, E.W. A Course in Bookbinding for Vocational Training. New York: Employing Bookbinders of America, 1927.

Palmer, E.W. A Course in Bookbinding for Vocational Training. New York: Employing Bookbinders of America, 1927.