C. Hammond Catalog, 1910. Courtesy of Gary Roberts, who runs the website, toolemera, which has tons of other fascinating trade catalogs, mainly woodworking, he has scanned from his personal collection.

Bexx Caswell, a recent NBSS grad, noticed that the Edith Diehl hammer I wrote about earlier is actually a blank book hammer. Bexx also also saw a similar hammer at Campbell-Logan Bindery in Minneapolis. The basic form descended from the French cobblers hammer I wrote about, but it is great to be able to trace its linage more precisely. The Diehl hammer that I own has some additional stamps (under the line that reads “PHLIA” it is stamped “CAST STEEL”) which leads me to think it is earlier than the one pictured in this catalog, since advertising cast steel is commonly more of a 19th century convention.

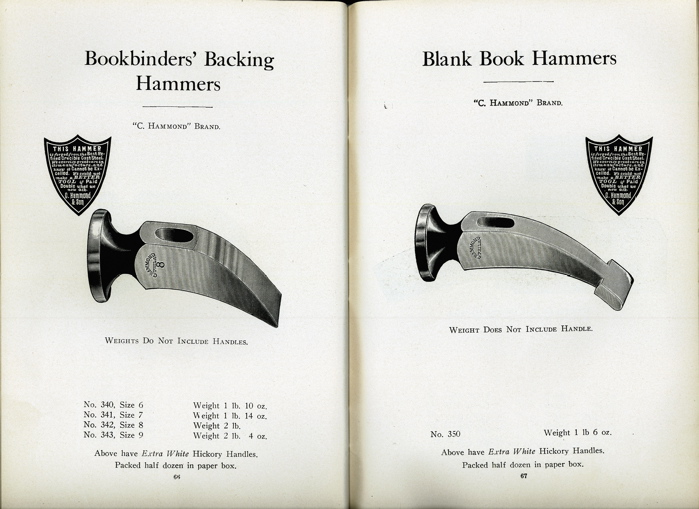

It is instructive to note that there were specialized hammers for Stationary Binders verses Bookbinders. The large, long peen may have been useful when forming the extreme arch many blank book spines have. Currently, most binders get by with one hammer, which mirrors the general decline in the diversity of specialized hand tools which continues to this day. Nineteenth century bookbinders also had specific hammer shapes for rounding, backing and, of course, beating.

Nice find, Bexx. However, Hickok catalogs in the 1920s and 1930s offered the same two styles under the names “Rounding Hammer” and “Backing Hammer.” I think these catalog descriptions are merely labels of convenience, not reflections of actual use.

Notice that the Hammond “Blank Book Hammer” comes in one size, lighter than ___any___ of the four sizes of “Bookbinders’ Backing Hammers;” also, by the way, lighter than either of the Hickok hammers in the same style. None of the Hickok weights (for both styles of hammer) are the same as the Hammond weights, but the range is approximately the same, just a little wider (1lb.4 oz. to 2lbs.8oz.). Between the two companies you could get the weight you wanted within an ounce up to 2 lbs. 4 oz.

I’m going to have to call you out on this one, Tom. Why would they call it a blank book hammer if it wasn’t for blank books, or at least it was in common use by stationary binders? How would this term be convenient?

Nearby chained books one couldt read this:

http://www.litterascripta.com/bibliomania/curses.shtml

LOL

Marketing, pure and simple. I checked a Hickock catalog and sure enough, they have a different name. It’s my guess that each company saw fit to name the hammer whatever they choose it to be. The buyer would know what was needed.

Hammond was a maker of hammers and related tools. It was in their best interest to apply clear labels to each and every product. Hickock made, amongst other products, bookbinders equipment (or subcontracted out such items as hammers for all we know) and so had no need to differentiate between labels of tools their customers already were familiar with.

Gary

Thanks Gary. So am I correct in assuming this was a common method of naming tools in other trades as well? Was a knife that carpenters used called a “tanners knife” in the trade catalogs? It still seems odd to me that a tool would be named for a long established trade, and have no relationship at all to that trade. Then again, I find many things odd…

Jeff… For common tools and machinery, there tends to be a common name, largely due to tradition. That said, it’s not unusual to find a tool carrying different names across trades and across companies, particularly for the lesser known items. Hammond offered only two binders hammers. Perhaps they were asked to produce a line of binders hammers by a blank book manufacturer and the name stuck? Or they simply wanted to apply a distinct name to their product to make it sound more special?

It would be interesting to see if there was a blank book bindery located near the Hammond factory.

Or perhaps Hickock felt not need to differentiate between the two, given that their customer base would know what was wanted. It’s any ones guess, lacking documentation. That’s part of the fun of old trade catalogs. They often raise more questions to be answered.

Gary

You are right about the dangers of speculating about how tools get names, but… I would guess it happened much, much earlier when bookbinding and blank book binding (stationary binding) became separate guilds and trades. The book structures became very different, and I bet the secretive guild education could lead to a very different terminology. Kind of the opposite of how cobblers and bookbinders use the same term –a “french knife”–to refer to two very different knives.

If you have any other trade catalogs that would be of interest to bookbinders, I’d love to get the links!

Is there any place that still sells a good, heavy backing hammer for bookbinding? Most of the ones I’ve seen lately for sale are very light in comparison to the nearly 2lb (and heavier) hammers in the Hammond advert that Jeff blogged about. Anyone?

Time to dig up the Hickok catalog and check some of the others to see if they offered binders supplies too. In general, catalogs for the book arts are few and far between. But I keep on looking for them.

Gary

Cool. Many of us would love to be able to see a complete Hickok online. I visited their (almost) defunct factory and wrote up a little piece about it- links in the resume section of this blog.

If only Hickok would deed their company records to a local university…

Jeff, I’m sorry I couldn’t get to replying for so long, and in the event Gary has said most of what I would have. One detail to add, though: the style that Hammond calls a “Backing Hammer” is the one Hickok calls a “Rounding Hammer.” What Hickok calls a “Backing Hammer” is what Hammond calls a “Blank Book Hammer.” Some catalogue names must be indicative of actual use, but I really think the balance of probability in this case is that the names are arbitrary. They look better in the catalog than “Bookbinders’ Style 1” and “Bookbinders’ Style 2.”

Mark, would French style backing hammers suit you? You might find what you want here as “French pattern blacksmith hammers,” in a good range of sizes:

http://hammersource.com/Blacksmithing_Hammers.html#TXTOBJ7D8611E151C34AB0

Or they may have something else that would suit.

Fair enough. One thing about the French blacksmithing hammers is that the face looks very, very flat, so you have to hit the book very squarely. You might want to spend some time filing or grinding a crown onto it.

We also don’t know what input, purposeful or accidental, the catalog printer had in the creation of a catalog. For all we know, the printer elected to change the name of the tool or some underling at Hammond did it. Perhaps some early marketing genius had his way.

I’m currently scanning a Peugeot Freres catalog, 1938. What looks to me like a standard bowsaw is an embalmers bowsaw. What we term plow planes are divided into a number of different configurations in French. Too bad I don’t read a lick of French any longer.

When it comes to naming things, at times I feel it is most proper to toss a coin.

Gary

I totally agree that once a term gets codified in a catalog it can determine future usage.

I disagree that most terms are as arbitrary as you seem to imply. In Bookbinding, at least generally speaking, most names describe what the tool or machine does or refer to how it is used: a “board shear” shears binders board in two; a “lying press” is used lying down, as opposed to a “standing press”, “finishing tools” are used for finishing.

Of course, what I find interesting are the terms that don’t fall into these general categories. Within finishing tools, there are “Pallets” and “Fillets”. I’ve got no clue where these come from. Tom?

I was not meaning to imply that terms are arbitrary. Rather, variations in nomenclature can creep in over the centuries to the extent that we no longer know from whence they came. Not being conversant in the bookbinders trade, I have to rely on woodworking. An example is the Table Saw. To date, no one has figured out exactly what this was used for. There are numerous references to this hand saw across many texts that relate to ship building. But, in almost all catalogs, the table saw is featured on the same page as a pruning saw with no clear distinction between the two, at least in the images offered.

I believe this particular association began with Disston and carried on through the other major saw manufacturers. That is all conjecture on my part as we have not a lick of information from which we can answer the question.

Lacking a shelf of bookbinders catalogs, I am helpless at assessing the ‘from whence’ or even ‘from where’ of the naming of these tools. Which means I really have to sit down and read Moxon on Printing, Nicholson and one other H C Baird title on my shelf (which seems to be the extent of my current early bookbinders texts).

[Advisory warning: ranting, raving etymological guesswork ahead]

[Did I say ranting, raving?]

Pallets and fillets— a nice example, since the French and English use the terms incompatibly, and some American binders follow French usage and some follow English usage. If you check a big Webster’s (I happen, by chance, to have one on my bench right now) the root meaning of fillet seems to be a thin band binding the hair, while the root meaning of pallet is a flat board, related to the peel used to remove drying paper from lines. All the binding meanings are reasonably consistent with these, but it is interesting that the binders’ fillet seems to take its meaning from the mark made, while the pallet takes it from the tool making the mark. And we can throw “roll” and “roullette” in here too. How about trying to untangle “glue brush” and “paste brush?” A lot of room puzzlement there.

“Plough” is a good example. Can you explain just how a bookbinders’ plough reminds you of a farmer’s plough? It beats me. A vertical plough is maybe a bit more like, but not very, and in any case the standard binders’ plough seems to predate the vertical plough by several centuries. “Beating hammer?” As opposed to all those hammers you don’t beat things with? “Bone folder?” Sure its used for folding, once in a while; but why not name it a “rubber-down,” which would reflect the more frequent use? How about the “pressknecht” used to support one end of the light fixed-screw German “handpresses?” What on earth does that refer to?

One can usually manufacture an explanation for a name, but is it necessarily true? Was an actual tub ever used to support a lying press? Maybe, but I don’t recall any evidence.

How about “spokeshave?” The metal one binders use is more like a small plane than the traditional wheelwright’s tool; and there is a tendency that has been noted for all shaves, no matter what their purpose, to have “spoke” added to the front of the name. By the time we finish modifying a 151 it certainly wouldn’t work well for spokes, even if binders made spokes. There is a historical origin to the term, but it reflects nothing in binding.

“Nipping press?” As it happens I was taught to use a nipping press to nip, that is to put on fast, hard pressure and take it off immediately, but from what I can tell not one binder in a dozen uses a nipping press to nip— it is used for slow pressure. And the copy presses that are usually called nipping presses aren’t just smaller in daylight; all the copy presses I have checked (a dozen or so) have double-helix screws, while the purpose-made binders nipping presses (by large daylight without yoke extensions) a single helix was used. English paring knives? I was told years ago that they are called “Swedish knives” in England, with the dubious explanation that they were made of Swedish steel (I can’t see Barnsley keeping a special steel for this one style).

I like a clicker knife for cutting out leather; this is more a general leatherworking knife than a binders’ knife, but Hewit does carry them for what its worth. This is one of the ones where no-one knows what the name means; the frequent explanation that the mechanism clicks doesn’t hold water because the name predates the mechanism. In fact, in the light leather industries the man who cut out the leather was a “clicker,” and no one knows why…….

The cases that have been irritating me recently are not binding tools, but they may be instructive. I frequently hear people refer now to a flat caliper as a “vernier caliper” or even just a “vernier” even if it has a dial or digital mechanism for the finest divisions; a Vernier caliper, of course, is properly one that uses a Vernier scale for this purpose, and is quite different (and harder to learn to use) from a dial or digital caliper. And recently the woodworking catalogues have taken to calling a turned-handle dovetail saw a “gent’s saw”, even though this term is well-established for a similar but smaller and finer-toothed saw that is also called a bead saw. Habit and ignorance play a part in the naming of tools…..

Uhhh…. Maybe getting carried away a bit here….. Let me take my frog pills… Sure lots of tool names reflect actual use, or historic use. Some don’t. It all goes back to the philosophical disputes of realist and nominalists in the High Middle Ages…. er, maybe I need another one of those frog pills….

Nice rant Tom!

One quick note, and I have a few more things to add later. Re: Tub. Diderot pictures an actual tub (looks like a half barrel) and a wood frame support existing at the same time, with the tub used for gilding.

Plate 5 shows this tub.

http://bookbinding.com/diderot/page5.htm

Plate 2 shows a frame tub, I assume for backing and cutting.

http://bookbinding.com/diderot/page2.htm

I’d always heard that the term “clicker” came from the sound of the cutting, since they would cut on tins. I think there are also references to this in bookbinding manuals.

Then again, we could return to using the long ‘s’ in our daily correspondence. Or turn to MTV for our baseline of proper word usage.

The extent to which we garble words leads me to believe a return to Latin might be a good response, although I don’t know how I would manage to translate a Yiddish phrase into Latin.

Or perhaps all of this is why I collect ephemera and books. Always looking for that peculiarity or answer to the burning questions, such as: Which came first, the Spoke (wooden shoe) or the Spoke (stick-like section of a wheel)?

Could I borrow some of those frog pills, please?

Nice catch on the tub in Diderot; I should have remembered. The explanation of the knife clicking on the tin cutting board does make historical sense; the clicking of the adjustable knife, and the clicking of the machine that is now called a “clicker,” both actually happen (and both are offered as explanations), but they are historically wrong. I’m pretty sure I’ve seen references to tin cutting surfaces in binding manuals, and in any case I have seen them in leatherworking manuals and even a few still in use, but I don’t remember the term “clicker knife” in a binding manual.

I still haven’t thought of the example I need (that is why I was ranting, because I didn’t actually have a good example): a binder’s tool, referred to normally by the name of a trade or subtrade, but not actually used by that trade. Maybe there isn’t one in binding; but I am sure I have seen a term like “bookbinders’ blurfl” for a tool we don’t actually use. I just can’t think of it.

Gary: I too am unsure how to translate a Yiddish phrase into Latin; but I’ll bet there is a Yiddish phrase for the problem.

I’ve also seen “clicker” knives referred to as “extension” knife blades in the current C.S. Osborne catalog:

http://www.csosborne.com/no460.htm

Palmer (1927) has a picture of one that he calls “Hyde Leather cutting Knife- Handle and Blade.” Riberhold (1978) also has a diagram of one that is called a “board cutting knife”.

I think I’ve also seen the name “stock knives” for changeable-blade clicker knives, but Dexter also calls them extension knives. The 1898 (I think) Barnsley catalogue reproduced by Salaman has a number of permanent-bladed clicker knives, sharpened on the concave but more slender and graceful than linoleum knives. This shape is still available from Dexter:

http:/www.dexter-Russell.com/product_line/industrial_cutlery/asp

about 2/3 of the way down, as “3-3/8 inch curved point shoe knife.” I’ve never had a bad Dexter knife; my usual bench knives are their 2″ stencil knives or the almost identical 2-1/8″ McKay stitchers, in this same part of the catalogue; and you can get proper forged carbon steel pallet knives from them, now a distinct rarity.

The naming of tools sometimes is just related to their use in industry I think. In the same way that my sister bottled the same oil in small bottles as Sewing Machine Oil, Chainsaw Oil, etc because the retailers needed to suit requests for oils to meet customers’ needs. Customers wanted an oil for a specific use, and did not necessarily have the confidence to apply a generic oil to a specific need. It’s the same with tools. A need for a tool with a rounded hammering face and a spikey thing can have many different names and uses, lots of the specific uses drop off over time, and the most popular name/use probably hangs on the longest.

Palmer mentions the best cutting surface for using with a straight edge and knife is, “…smooth flat zinc tacked down to a flat surface like a table top.” (p. 137)

Palmer, E.W. A Course in Bookbinding for Vocational Training. New York: Employing Bookbinders of America, 1927.

“The Shoe Industry”: Allen, F. J. 1916 : Clicking – the cutting of shoe uppers by machinery

On the other hand, zinc was used before we began to recycle old truck tires as cutting mats.

A clicker by any other name…

Gary

John Waterer’s books, reflecting British mid-20th century trade leatherworking, talk about the clicker knife and “clickers” as hand workers. I would guess that Allen is American?

Benjamin Allen was Investigator for the Vocational Bureau of Boston. How’s that for a title?

Gary is on this post 🙂

Whoops, you are right. Are you referring to the photograph? The line drawing is in copyright.

Hey Gary- I finally upgraded my pdf reader, so could finally read the Hickock catalog you have posted:

Click to access hickokCatc1920.pdf

Both Hammond and Hickock call the same looking hammer a “backing hammer”, but Hammond calls the other a blank book hammer, Hickock a rounding hammer.

I have a suspicion that Hammond was marketing the blank book hammer specifically to that portion of the trade.

Makes sense- around this time offices shift to typewriters, carbon copies, filing, etc. as record storage, rather than blank books.

We just got a copy of a Slade, Hipp, and Meloy catalog at the American Bookbinders’ Museum with a “Diehl type” hammer listed as a “Forwarder’s Hammer.” Its the only hammer in the catalog, and there is just one (unspecified) size. The date is 1899-1911, from the address on the title page (139 Lake Street, Chicago). On the basis of the catalog they were general binders’ suppliers, much like Gane Bros. & Lane, picking up major supplies and equipment from a variety of sources. I don’t know if they did any manufacturing, though I have seen finishing tools marked with their name.