Thomas D. Conroy – a friend and colleague – died on November 11, 2025. He was a bookbinder, woodworker, book historian, toolmaker; basically one of those people who knew something about everything.(1) Needless to say, his extensive knowledge often resulted in impromptu discursive lectures, accompanied not only with citations, but sometimes extended quotations from memory.

Unusually, his wide ranging interests and experiences would often coalesce into useful information. He was my go to source for identifying all types of tools. Once I queried him on a “whatsit”; or unknown tool. It was an 18 inches inch with forged octagonal shaft, flattened and hooked at one end, a brass ferrule, and the other end extending through a beautifully turned wood handle.

Tom identified it as a stuffer of some sort, likely for horse collars. But not after a lengthy, though fascinating, unasked for treatise on the history of golf ball stuffing materials and tools. I’m sure Jack Nicholas couldn’t have given a more through explaination. That was Tom.

His expansive and free-range mindset was cemented during his undergraduate years at St John’s University. Only half-jokingly, he once complained that St John’s had ruined his life; convincing him to accumulate ideas rather than money. Most of his adult life he lived simply but comfortably in Berkeley, CA. He obtained an MLS from UC Berkeley.

I suspect his scholarly rigor didn’t come from formal education; instead it sprouted from his stubborn autodidactism. He was an autodidact’s autodidact; fusing the history of books, woodworking, craft, general mechanics, and god knows what else into his unique take on things.

His hard earned knowledge was freely shared. Sometimes his comments on blog posts exceeded the length of the original. I had to be careful when corresponding: a seemingly simple question could provoke a comprehensive answer a few hours later: a little slower than AI, but more accurate. I didn’t want to take advantage of his intellectual generosity by constantly pestering him.

Tom took a well-deserved pride in his writing. We primarily corresponded through writing, first in letters and later through email, and we usually discussed things, not personal history. I don’t think it was because we were reluctant to share; it’s just that we were both more interested in things outside of ourselves. Are writing chops genetic? He never mentioned to me his grandfather Jack Conroy, was a self described “proletariat worker advocate” and professional writer, with a Guggenheim fellowship and an armful of published books. Tom had a tremendous influence on my own work and as our relationship progressed over 30 years, I changed from a fanboy to a peer – at least in my own mind.

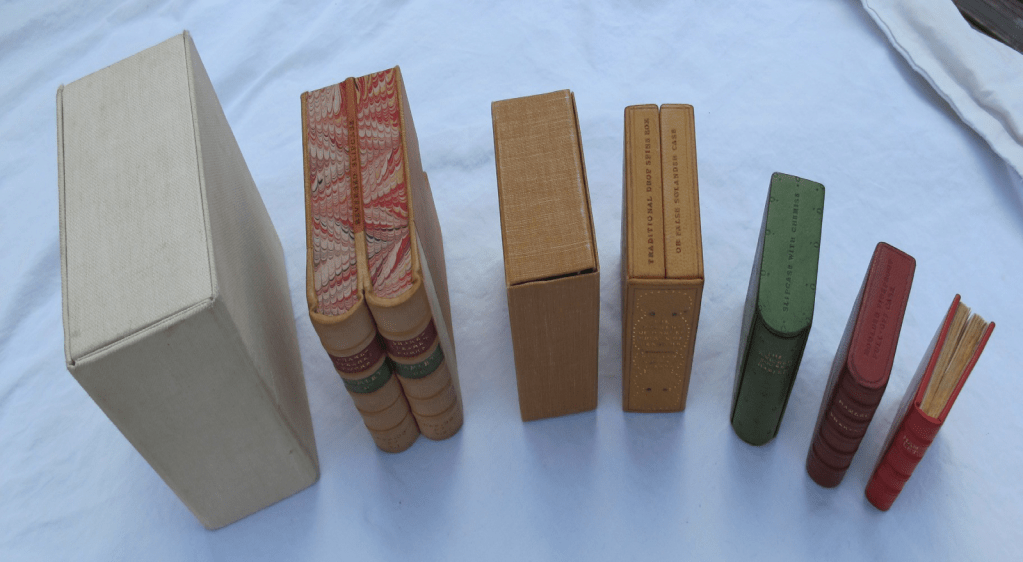

Not content with theoretical knowledge, he was also a maker: working in metal, wood, paper, and leather. These converged in unexpected ways, guided by his Conrovian cosmology. (thank you John DeMerrit and Dominic O’Reily for coining this apt term!) One example was his clever set of nesting boxes explored the range of book housings for a single book.

Another example is a group of bone folders he had shaped. They looked unfinished and crude to me, a puzzling departure from most of Tom’s work. He carefully explained that their form was a direct result of function, along with the philosophic underpinnings of this type of craft work. His self-imposed challenge was to alter the original shape of the bone as little as possible to achieve a functional tool, instead of compulsively polishing every surface.

He loved all types of tools. A set of band sticks in a virtually airtight leather case was another tool he made that I particularly admired. He explained that he had copied them from a set owned by another binder, reportedly in order not to steal them! True tool lust.

Tom was a prolific author, despite often complaining of writers block. One of his many contradictions. If you are not familiar with Tom’s work, here are two recommended articles.

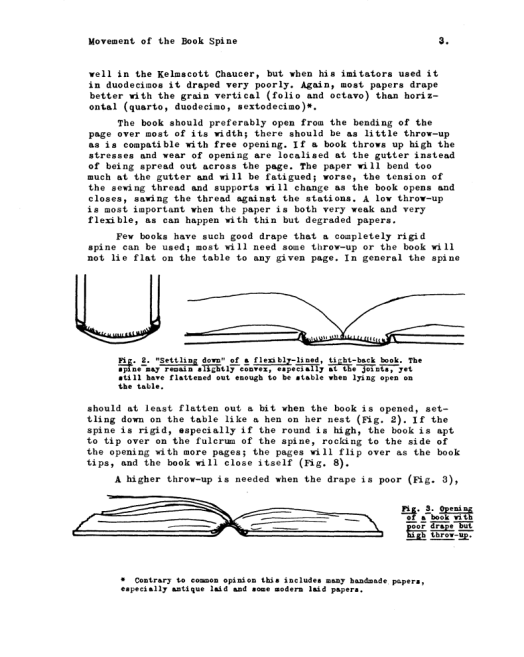

First, his 1987 “The Movement of the Book Spine”. It is essential reading for any bookbinder or book conservator. In it, he organizes the craft knowledge of bookbinding spine engineering into a rational system. He acknowledges that this is theoretical: it is up to others to test his hypotheses. And you know what? Despite some minor disagreements I have, they hold up really well.

In 2023 he wrote “Bookbinding in the time of Cholera”; the tale of a sewing key and a coincidence that lead to its identification. It’s a great read and demonstrates how disparate bits of knowledge can coalesce once critical mass is reached.

The last time I visited him, we talked for a few hours about books and tools and associated tangents. He was apologetic for his occasional lapses in memory and general fatigue, yet was prolific to the end; publishing two articles in the 2025 Suave Mechanicals 9 and working on a final uncompleted article about bookbinder’s backing hammers.

Before I left his Berkeley house, he gifted me a pair of original Fay dividers. As I stepped down the stairs of his weather eaten front porch he hoarsely shouted I could find more information in appendix three of Kenneth Cope’s American machinists tools.

As typical with Tom, tracking these citations expanded into related patents, like the beautifully shaped Steven’s dividers. More interesting things to research. Endings are messy. Tom is gone. I’ll miss him.

Footnote

- Tom was also a lover of footnotes. Occasionally they even exceeded the length of his primary text. This mirrored his digressionary speaking style. This one’s for you Tom, apologies for the brevity!

This is very sad news. I met Tom Conroy once in our library workshop in Florence, when he came to study the Florence Flood, and he ended up giving me more information than he received from me—as was typical of him. He very generously spoke about Stella Patri, a subject I knew almost nothing about at the time.

That sounds like Tom! Some of Stella’s archives are at the bookbinder’s museum, and I noticed a couple of Chris Clarkson letters online: https://hub.catalogit.app/american-bookbinders-museum/folder/stella-patri-collection