By Tom Conroy

The very way to gain a taste

For eating glue and spoiled paste…

Then back to live in grimy rooms,

As cold as eyes, as small as tombs,

And, writhing, die before you oughter

Like Wright and Wickwar, of Broad Street water.

—–Struwwelbinder

PRELUDE

In late August 1854, cholera again visited London, as it had in 1832 and 1849, and it settled down for a good long stay in Soho. Victims leaked fluids grossly and continuously, but if they drank water—-or gin—- it didn’t help them or ease their misery. The special horror of cholera was enhanced by its irrationality: it never attacked everyone, but it might attack almost everyone in an area a block square. Or it might checkerboard an area, or it might spare all the residents of a house —-except for those in one room. No one understood why or how it chose where to strike. Diseases were miasmas, air-borne, weren’t they? A miasma should attack everyone. By the time the cholera moved on, a quarter of the people who caught it had died.

Be patient. This is, I assure you, a posting about bookbinding history, or at least about bookbinding tools. But you will have to wait a bit.

John Snow, a local doctor, had studied the nature of cholera during the 1849 outbreak. He went house to house and room to room, questioning the sick, the recovered, the people who never caught it. He asked about where they went, where they worked, where they played. He asked who they met. He asked what they drank and what they ate. He asked about the days that they, and their dead, had caught the complaint, asked when others around them caught it, asked about the days of the week and the phases of the moon. By the end he had put together, and later published, a remarkably detailed account of the people of the district and how they acted. And still cholera was irrational, not to be predicted, impossible to understand.

But Snow had noticed something, and he had a theory. Water was run in pipes to houses and to businesses, and in Soho the pipes were filled and maintained by competing private companies. They competed on clearness and on fresh taste, and on price. It seemed to Snow that cholera loved to attack people who drank or used water provided by the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company, which drew its water straight from the Thames in London, where it was filled with the filth of the city; but cholera avoided those who used the water of the Lambeth Waterworks Company, which piped its water from the Thames above London where water was relatively clean. Snow documented this, case by case and house by house and business by business. To those willing to look at his data, he had proved that, whatever actually caused cholera, it was water-borne. It was carried by fouled water.

He had a demonstration more vivid in his hand, and something useful to be done: in 1854 he found that the cholera outbreak was most ferocious among people who used a public pump which sat on top of its own well outside 39 Broad (now Broadwick) Street, a few steps down from Number 63 where Bernard Middleton would set up his first bindery a century later. There were a dozen of these public pumps in Soho. At most times water from the Broad Street pump was known for clearness and good taste: it was not hooked into the piped water system, and did not draw from the Thames, but had its own well sunk deep into the gravel aquifer. Its well, however, was only three feet from a shallow over-used cesspit that overflowed from time to time. Snow thought that when the cesspit overflowed, the “cholera poison” was carried from it down into the well water. With his evidence in hand, Snow went to the Board of Guardians of St. James’s Parish on September 7 and asked them to chain up the Broad Street pump. At first they refused. Snow was not a good speaker. Perhaps they made it clear that they would laugh at him, except for the pile of the dead waiting to be buried. Cholera was a miasma, wasn’t it?

The official story— Snow’s own story— is that Snow finally convinced the Guardians, and they shut the well down the next day. They reopened it later, when the epidemic had passed (cholera was a miasma, air-borne, everyone knew that). My imagination sees something else happening.

Doctor John Snow was a Victorian. I think he walked over to Broad Street, took off the handle and chained up the pump himself, and took the handle home. Many secondary sources say flat out that he did so. The outbreak was already dying down on Broad Street because three-quarters of Soho’s residents had already fled the district; but disabling the pump turned off the cholera like water from a tap. The whole outbreak lasted less than ten days, but in that time 610 people had died, 127 of them on Broad Street.

John Snow’s action on Broad Street, whether the bit of idealistic vandalism of my imagination or the staid, slow, respectable movement through official channels of the public story, is now considered the origin of the sciences of epidemiology and public health, and it only took thirty or forty years before people realized that he had done something good. In his own day he gained more fame as Queen Victoria’s first anesthetist. In 1853 she wanted ether, Snow wanted to give it to her, and the Queen of England had enough clout to brush aside the medical establishment’s ideas about natural childbirth and God’s blessèd pain.

THE KEYS.

No one else will die of cholera in this essay, beyond those who got it in 1854.

On the morning of October 7, 2006, San Francisco-area bookbinding teacher Anne Kahle was one of the first through the door at the sale of binding tools, materials and books from the estate of Joanne Sonnichsen. Anne was born in England and trained by Arthur Johnson, and in 1960 she was one of three prize winners in the 26-and-younger section of the Thomas Harrison Memorial Competition (the predecessor of The Bookbinding Competition); but her career as a design binder had a big setback when her father took a faculty position at the University of California and she moved to Berkeley with her family. By 2006 she had been teaching English-style bookbinding in Berkeley for almost forty years. Joanne Sonnichsen was a design binder of international activity and reputation, well known and respected in France, who had been an early adopter of innovative and historically inspired book structures. She was trained in San Francisco’s French-derived bookbinding tradition, and was a Francophile in all things. She and her husband kept a flat in Paris and spent part of each year there. In France she had spent much of her time trying to explain the new American bookbinding to the French—-in America she taught traditional French technique and standards to Americans.

At Joanne’s estate sale, the first table Anne looked at had a heap of several dozen sewing keys, with something a bit odd about a few of them. Anne, long practiced in flea markets, yard sales, and (in her youth) boot sales, scooped up all the keys without a second glance, bought them all at the asking price, and didn’t look at them again until she got home. A binding teacher always needs sewing keys, she says, and the dozens of common modern keys were bound to be useful as well as making excellent cover for whatever she had seen.

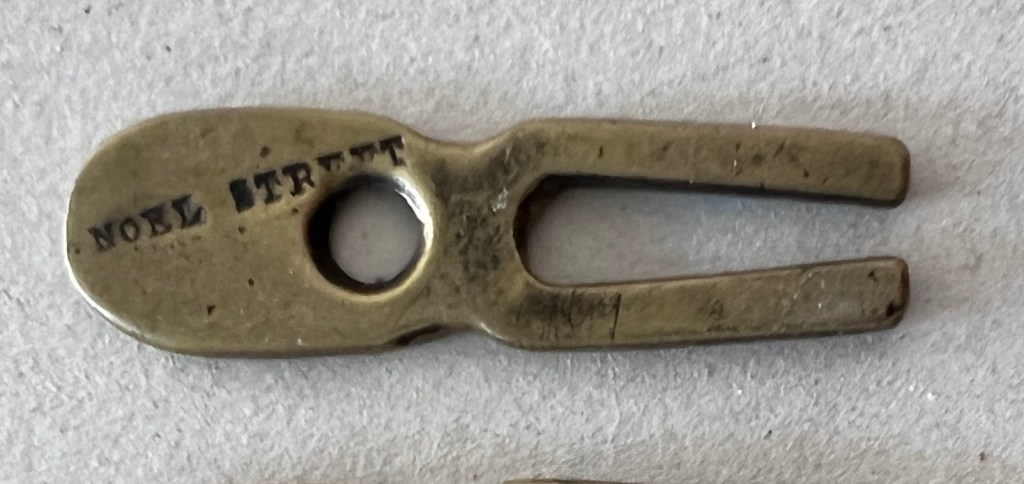

But just what had she seen? Three keys a lot bigger and fatter than modern ones, and a bit blodgy, not excessively straight or precision-ground. Heavy. Cast brass, not stamped, shined up recently by a neat freak with a buffing wheel, but looking—-old. Very old.

Dating small bookbinding tools is rarely possible because there are few pictures of them before the 1880s, and the early pictures were reused in catalogues and manuals for many decades to avoid the cost of engraving new ones. But these newly acquired sewing keys might be datable, I thought when I saw them, because they were marked “J. Wright” on two of the six broad flats, “Noel Street” on another. English language. No city, that probably meant London, “the flower of cities all,” the default, the center of gravity. Ownership mark or maker’s mark? We’ll see. To find out when and who J. Wright was, meant checking the London city directories (“Kelly’s Post Office London Directory”) year by year through the 19th century to see if a J. Wright would turn up on Noel Street, if there was a Noel Street. The slog began. He was there, in Soho, in the 1840s and early 1850s all right, down through 1854. Then he was out of the directories for a year. Was this a terminus ad quem, an upper bound, a before-which-limit to his dates of activity? In 1856 there was no John, but an address for his estate and for his widow as executor. Definitely a limit! And then…

Something familiar about the name Wright… and 1854…. eventually it came together by increments so small that I barely noticed the point when I remembered what I already knew.

Between August 31 and September 8, 1854 bookbinders John Wright of Noel Street, Soho, John Wickwar of nearly Poland Street, and, my flickering memory told me, twenty-seven members of their staffs and families caught or died from cholera. By the documents, five employees of Wright’s died with him, three with Wickwar. John Wickwar’s infirm mother now lived in another part of London, but she liked the taste of water from the Broad Street pump; when Wickwar’s brother William came into town to see his dying brother (he came too late) he had made a special effort to bring her some Broad Street water after his visit. She died of her little treat. So did William. Those sewing keys had a terminus ad quem all right, in spades.

CODA

I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night

As big as you or me,

I told him, “Joe, you’re ten years dead.”

“I never died,” said he.

“I never died,” said he.

We like, we humans, stories with endings. Some endings are happy, some not; but drawing a black line of death under the stories of two commonplace London bookbinders has a narrative cogency that—-isn’t at one with all the facts. John Wright and John Wickwar and dozens of their friends and families may have had their own lives truncated, but the stories go on. Once you start to look for that terminal black line, it runs from you, in little spurts, in gaps in the narrative, in unexpected facts that start stories all their own.

Ten years ago Philippa Marks, preparing her own essay on bookbinders and the Broad Street Pump, searched for the outbreak’s consequences in the great John Jaffray Collection of primary-source documents and ephemera on English bookbinding. She learned that despite the disappearance of—- “all my pretty chickens and their dam” in the great outbreak, despite the death of Wickwar’s mother and brother and his cheeping workers, and despite Wright’s grieving widow having to act as his executor because, the imagination says, no one else was left alive to do the job, despite all setbacks, both businesses recovered after 1854. I wonder: How?

Wright and Wickwar were not commonplace trade binders scratching out meager livings in decrepit, run-down Soho, as I imagined when I wrote Struwwelbinder. Maurice Packer’s directory Bookbinders of Victorian London shows that by 1854 Wright’s bindery used four buildings on one block of Noel Street, Nos. 14-16 and 21. “Three addresses always inspire confidence, even in tradesmen,” said Lady Bracknell. Charles Ramsden, whose terse directories almost never give three words of English prose to anyone, says that he was “A binder of the highest order but in the main falls outside our period.” (London Bookbinders 1780-1840). This praise was not unmerited.

In August, 2023 the rare book dealer Philip Pirages offered a shockingly intense, no-shortcuts, glittering binding by Wright, one volume of a two-volume set whose other was lost when being shipped to Pirages. There’s a story that is working itself out somewhere, leaving a measure of sorrow for lovers of fine bindings. There is other estimable work by Wright in the British Library’s Database of Bookbindings. Wright’s business remained at 14–16 Noel St. until 1863; in 1864 it was replaced by another bookbinder, Walter S. Hammond, who traded there until 1887. The site was leveled in 1897 to make way for the French Protestant School; which in turn was closed in 1939.

And Wickwar! Things to be told seem to cluster around him, then to retreat from study like water from the lips of Tantalus. Wickwar was able to turn out an intense bit of glitter, a plate in Ramsden shows it. But John Wickwar, who seems to have begun life as a papermaker in his father’s mill, turned from pure bookbinding to making leather-covered despatch boxes for the British government—the iconic “Red Boxes” that are given to all new cabinet ministers, that appear in pictures of the Queen, that the Chancellor of the Exchequer waves in the air to signify that the year’s budget is ready. Most bookbinders make boxes from time to time. Wickwar’s made a “red box” for William Ewart Gladstone in, it would seem, 1853. I wonder if the journeyman who made it died in the outbreak? Gladstone’s budget box remained in use until 2010, and looks it: the red ram’s skin covering is shabby with the handling of 51 chancellors. May all our work endure to be so shabby! Wickwar’s made a red box for Prince Albert (probably) around 1860 (probably). Wickwar’s made a red box for Winston Churchill; that one was sold a few years ago for £160,000. And Wickwar’s are still in business today, still making red boxes (and little else, it seems), and deadly quiet about themselves in the classic British manner.

As best I can tell from primary sources that Philippa Marks assembled, after the year of the cholera the Wickwar bindery at 6 Poland St. was taken over by John’s brother Francis; old John’s nephew John found room to set up his dental office in the underpopulated building— a grim aftertaste to the disease. After Francis the firm was inherited by Francis’ grandson Arthur Spain. Wickwar & Company was still, according to Packer, at 6 Poland Street in 1897, a few years after the site was rebuilt or at least refronted with a great expanse of large glass windows which would be ideal for a bindery if only they faced north (they don’t). At some point Wickwar’s was at 98 Jermyn Street (it is not clear if this was in addition to or after the Poland Street location) amid many posh haberdashers, a location which would have been good for selling dressing cases and other boxes; so the shift in products is hinted at by the new address. I lose track of the company for the whole twentieth century, until it pops up today with a tight-lipped website with lots of words but little real information. It is probably at least a century since anyone asked them to bind a book. A big stream of Wickwar’s murky loss to the bookbinding world disrupts my neat black line under the London cholera outbreak of 1854.

And, in a very small rivulet of unfinished-story-ichor, somehow three blodgy, oversized sewing keys took a century and a half to find their way from England into the bindery of a Francophile American design binder, and were sold on her death with their patina scrubbed off the brass and their histories lost. The keys are sitting by me on my bench, on loan from their owner for seventeen years while I was supposed to be writing a brief note for publication about them. I ought to get them back to Anne Kahle now that the note is written. But there are still all those stories to look into. And I still haven’t figured out just what I might learn about the technique of Victorian bookbinding from the sewing keys.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Readers perceptive in the ways of books will realize that this is a rapidly-constructed ruminative essay, relying heavily on memory rather than meticulous research. The London cholera outbreak of 1854 was just one incident in the larger pandemic of 1846–1860, and it was a key step in the development of modern medicine. Literature relating to is very extensive indeed (at least seven significant books on it have been published in the last twenty years) and I have barely scratched it. This list includes the sources known to me concerning the bookbinders overtaken by the epidemic; some but not all of the general sources used in writing this essay; and some works that will suggest lines of investigation that I have not followed.

Numbers given here are approximate. Every source I have looked at gives specific counts for all the statistics, but in every source the numbers differ slightly, right back to Snow himself. For good reason. At times Snow’s statistics are for Broad Street, at times for the Pump’s area of distribution, at times for Soho, at times for all of London. At times he is comparing deaths, at times cases. At times he is looking at the whole time of the Broad Street outbreak, at times new cases during the outbreak, at times deaths during the outbreak, at times cases that started during the outbreak but ended in death much later. Snow kept this all straight and was explicit about what went with what, but not all students have had the patience to follow him in detail through the pages through which one of his lines of reasoning will play out; nor, at times, do I. The numbers I give in this essay are good enough for book arts.

T.C.

Marks, Philippa. “John Snow saves Soho bookbinders.” (British Library) Untold Lives Blog (15 March 2013): <https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2013/03/john-snow-saves-soho-bookbinders.html>; accessed October 2, 2023.

Middleton, Bernard. Recollections: A life in bookbinding. New Castle, Delaware and London: Oak Knoll Press and The British Library, 2000, p. 35.

Packer, Maurice. Bookbinders of Victorian London. London: The British Library, 1991.

Ramsden, Charles. London Book Binders 1780-1840. London: B.T. Batsford, 1956. (My copy of this book was bought at Joanne Sonnichsen’s estate sale).

Snow, John. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. 2nd. ed. London: John Churchill, 1855: <https://archive.org/details/b28985266/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater>; accessed October 2, 2023. The Broad Street Pump outbreak is discussed on pages 38–55.

Vinton-Johansen, Peter. “Bibliography (Unpacking Essays).” to Cholera in St. James: Experiments in narrative history, historiography, and more…; <http://johnsnow.matrix.msu.edu/broadstpump/bib/>; accessed Oct. 12, 2023. “This [web]site is now undergoing reconfiguration and reconstruction, reflecting a shift in priorities since (1) the publication of Investigating Cholera in Broad Street (a documentary source book); and (2) current preparation of a video series featuring the 1854 London cholera epidemic…”

“Broad Street Cholera Pump.” Atlas Obscura:The definitive guide to the World’s Hidden Wonders: <https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/broad-street-cholera-pump>; accessed October 12, 2023.

” D’Arblay and Noel Street Area.” BHO| British History Online (Survey of London): <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp230-242#h3-0014>; accessed October 10, 2023. Most of Noel Street has been demolished and modernized, including Wright’s premises at No. 14, 15, and 16 ; but the Survey has a plan and elevation of the recently demolished No. 11, which was probably similar.

“Poland Street Area.” BHO| British History Online (Survey of London): <https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp243-249>; accessed October 10, 2023.

“The Despatch Box.” Wickwar Est. 1750: < https://wickwar.com/>; accessed October 11, 2023.

“Welcome to the John Snow Society.” The John Snow Society: <https://johnsnowsociety.org/>; accessed October 12, 2023. Especially important as a bibliographic starting point.

“Will of John Wright, Bookbinder of Soho, Middlesex.” The [British] National Archives: < https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D47189>; accessed October 10, 2023.

Wikipedia entries consulted include “Despatch Box”, “Red box (government),” “Broad Street Cholera Outbreak,” “Barrow Hepburn & Gale,” etc.

FOR BERNARD MIDDLETON

“First of us all, and sweetest singer born”

who I never knew well, but who I miss very much,

never more constantly than while writing this essay.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to Phillip Pirages for permission to use the photograph of John Wright’s binding on Dresses and Decorations of the Middle Ages vol. 1 (London: William Pickering, 1843); to Philippa Marks for sending her research notes and primary materials on John Wickwar and his family, for reading this essay in draft, and for general support; and to Jeff Peachey for photographing the John Wright sewing keys, for making space available on his website, and for coming up with a title that made the rapid writing of the essay inescapable.

Tom Conroy is a bookbinding historian and retired book restorer, toolmaker, and fine binder in Berkeley, California. His memory stretches back to the long-lamented Great Craft Revival of the 1960s, in the days when dinosaurs walked the earth.

What a lovely surprise this morning to read Tom Conroy! Such a wonderful conversational tone. It sounds exactly like one of his front porch, workshop lectures – I can practically feel the sun on my face as I look over his shoulder, while he arranges a pop-up museum of tools on the ledge.

You nailed it!

Sarah, What lovely comment to get as a start! Thank you. Tom.

Dear Tom and Jeff

What a gift in my inbox! Thank you for such an interesting diversion and essay in history of bookbinding and London. Excellent and the mention of Bernard was so lovely. I was lucky enough to spend a whole day with him at his home and bindery

What a genuinely sweet and knowledgeable man, who has had such an influence for the better on the modern expression of the work in so many hands and minds, he set the tone of generosity among the many towards fellow students in the field.

Kath Thomas

Tom,

First of all thanks so much for this wonderful story and research! I still have two questions.

1. How were these made? The voids look like casting, but the overall sizes and thicknesses are quite different. A remains of a small hole drilled in the legs of the middle one indicates there was some drilling and sawing. The outer shapes look filed to me.

2. Do you think these were made for sale? The name stamps must have been made from steel, not a usual brass logo. Did Wright use the same tool to sign bindings? Even more puzzling is the street stamp, which strongly indicates items for sale. Lots of tool owners mark their names onto tools; far fewer add an address.

Jeff

This will come in little bits. [Well, great big little bits, maybe} For (1), what I have is less an answer than context. I think that the differences between the keys are a sign of small-batch production, with the three keys coming from three batches. A small foundry, like a bellfounder, could easily have made up a casting of a dozen or so keys at a time, from one wooden pattern, making a dozen at a time as cheaply as just one. Small foundries were already in the circle of indirect binders’ suppliers, since they made cast brass blanks for finishing tool makers. The marks on the keys are very similar to the marks on mid-19th century finishing tools, in size, letterform, and depth of strike. I’ll bet that when binders needed more sewing keys, they went to a toolcutter, who could have knocked them out without thinking twice. As late as the 1960s, Blewitt’s in Southwick, where P. & S. were apprenticed, bought cast blanks for finishing tools from a bellfounder.

The obvious alternative to casting would be cutting from sheet brass. The context consideration here is: when was sheet brass developed as an article of commerce? That in turn depends on the development of the rolling mill and its application to brass, which in turn depends on the development of brass alloys that could be reliably be shaped by —“squeezing”, my mind is wobbling, I forget the proper term. Copper alloys are apt to workharden rapidly, which means that extended [squeezing] operations usually result in cracking and shattering on the second or third pass through the rolls. Rolling mills would have developed for commercial production of ferrous metals long before they became economical for copper alloys. I found one very shallow history of sheet metals on line () that says “Almost two centuries after the first rolling mill was developed, the process for creating sheet metal was perfected by Jean Pierre Droz in 1770. Droz was a coin and metal engraver….By 1851, sheet metal production was underway in America and Europe on a large scale. A 6 meter long and 11 millimeter thick piece of sheet metal was displayed at the British Great Expedition.” Let me pause to contemplate the Crystal Palace Expedition for a moment (maybe it was sent out to get the crystals?)—well, we all make misprints, and I have made bigger ones. Back to the point: this web page is talking and thinking mostly about ferrous metals, not brass, so even with an effective introduction in the first half of the 19th century, rolled brass was very likely still an exotic and possibly expensive material in the 1850s. If I were looking into the issue seriously, I think I would start by looking up the sections on brass manufacture in Tomlinson’s Cyclopedia of the Useful Arts, and I would try to tap into the conservation of clocks and watches and the history of watchmaking to see if they have produced any studies of the raw materials for closksmiths in the 19th century. In fact, I think I will go and try to hunt down an online copy of Tomlinson (in my experience, a shy woodland creature in the bosky glades of the Internet Archive—I ought to just bookmark the damn book, and be donen with it.) I’ll be back in a bit on question 2.

Tomlinson is a great idea! The 1852 ed. I have is largely proportions for casting, but does say it is cast into sheets then rolled or drawn into wire. And the bookbinding section has a sewing key that looks virtually identical to yours.

Yes, in light of Tomlinson I think that cast sheets would have been common enough that sheet brass wouldn’t have been an exotic material by the 1850s. And “Muntz metal,” a 40%/60% sheet brass for sheathing ship bottoms, was made by rolling and was invented in the 1830s. I think, though, that the hypothetical connection of sewing keys and finishing tool makers is important, as is question 2, of who was selling what to whom. But my mind is full of cotton at the moment, I’ll come back to it when I’ve had a nap. Nice find in the bookbinding entry in Tomlinson.

Jeff, as you know you recently forwarded an interesting communication from Catherine Goulding to me about Wickwar:

“I felt that I had to get in touch as I was very interested to read about your research into the bookbinders of Soho. I am a direct descendent of the Wickwar family through Francis Wickwar, brother of John and William. It is quite an unusual name here in England. I have visited 6 Poland Street and you can still walk into the courtyard behind the shop and get a feel of what it might have been like. Thank you for such an interesting article and for preserving the craft of bookbinding and the books themselves.”

My reply to her incldes an important correction on a point of fact which, in my haste, I got wrong, so I’m copying it here:

“Thank you so much for your note on my guest blog posting on the Broad Street cholera outbreak. I should correct an error that has already turned up in what I wrote: it now seems clear that William Wickwar did not carry a bottle of Broad Street water home to his mother, who died of it. I apparently mixed together two separate stories on Page 44 of John Snow’s book: One account is of William Wickwar who came in from Brighton to see his dying brother, arrived too late, and did not view his brother’s body; ‘He only stayed about twenty minutes in the house, where he took a hasty and scanty luncheon of rumpsteak, taking with it a small tumbler of brandy and water, the water being from Broad Street pump,’ then proceeded on to Pentonville, where he died the next day. The identification of this as being about the Wickwars is made certain by accounts in contemporary bookbinding periodicals, now in the Jaffrey Collection in the British Museum. The other account is of a lady in the Hampstead district: “I was informed by this lady’s son that she had not been in the neighbourhood of Broad Street, for many months. A cart went from Broad Street to West End every day, and it was the custom to take out a large bottle of the water from the pump in Broad Street, as she preferred it.” Snow says directly, however, that the lady was “the widow of a percussion-cap maker.” I must have read Snow’s page too hastily, or misremembered it, and mixed the two stories together. As I said in my afternote, the blog posting was done largely from memory, and I did not try to hold to the standards of checking that I would normally have done.

I’m very interested to hear about the yard of 6 Poland Street. Researching from California makes me treasure little observations like this. I found the entry for that block in the Survey of London, and it would appear that the address was rebuilt in around 1893. I wonder, though, if it was rebuilt from scratch or just re-faced. There are also several estate agents’ pages for rentals of upper-floor flats in the building, so I was able to see good photos of the current frontage. Its big glass windows would have been very modern and up-to-date in the 1890s, and they are also just the kind of natural light that most craftsmen and artists long for, except for the fact that they seem to be facing west, not north. One source that I don’t exactly trust [Packer’s directory] says that Wickwar’s was still at 6 Poland Street as late as 1896, and I can easily imagine a prosperous firm having the frontage redone in up-to-date style with better lighting. It is less obvious why the firm might move just a few years later.

After 1896, however, the difficulties on trying to research from California kick in. I completely lost track of the Wickwar firm and the family after 1896. My basic source for this kind of research is the London Post Office Directories, which can be used to obtain an address each year, which becomes the skeleton of the story. Unfortunately, I know of no extensive run of the P.O. Directories west of Chicago. For the period before 1850 there is a vast microfilm edition of most London directories, with one copy in San Francisco and probably others in Salt Lake City and points east, but only scattered single years in hard copy after that. Around 15 years ago a CD-ROM edition was published of the full run of London P.O. directories, but I haven’t been able to locate a copy of it. It would be possible to do the research despite the problems with sources (I have done it in the past), but that becomes a serious long-term effort, far more than would have been appropriate for my brief informal posting. Another possibility would be to use the online resources available for genealogical research, which was a very good option ten or fifteen years ago when there were several competing sites with no fees or registration requirements; but one company has now managed to dominate this field, and they have pulled up the fees and registration requirements until they have become too high for, again, a brief informal essay. But I must confess that my failure to get good sources for the 20th century left me with a degree of curiosity about how the Wickwar story played out. I found so many journalistic accounts of the red boxes—and there was so little hard information in any of them!

I hope I haven’t bored you by rambling on about research methods for so long—I am 71, and aging fast, including what might be described as verbal cholera.

All useful information. If you do think you have verbal cholera; all the standard 19th century cures may be applicable: bleeding, purging, and opium.

Well, I do have opium. (A bit of tincture of opium left in an inch-high bottle, which was q-tipped onto my gums when teething and the when my adult teeth came in. I sometimes woner if the same bottle was used by my grandmother on my mother, back in the 1930s.)

I’ve got a longer secod letter in hand from catherine, but I don’t know if her permission to publish includes the second letter; and there is probably a point where enough is enough. Not sure what to do yet. Oh, and I think I hahd some reaction to your first reply that I hadn’t sent in yet. But I’m getting distracted by other projects. Tom